Early SAAD

| 1930 - 1950 |

In the early 1930's Stanley Drummond Jackson was a dentist practising in Yorkshire. He was the son of a dentist. In those days dentists largely employed general medical practitioners to provide nitrous oxide based anaesthesia for their patients. Generations of children grew up to know the dread of "gas" at the dentists... As a young dentist Drummond Jackson or ‘DJ' as he became known later, was appalled at the inadequacy and poor quality of general anaesthetic provision for dentistry.

Stanley Drummond Jackson

SAAD Logo 'Abolish pain to conquer fear'

SAAD Logo 'Abolish pain to conquer fear'

In a way that would now be considered totally unacceptable but was then completely permissible, Drummond Jackson experimented with new intravenous anaesthetic drugs given by the “venal route” and introduced from Germany and America. By trial and error, he developed a method of intravenous anaesthesia that worked providing fast onset, variable operating time, and quick recovery. DJ was enthusiastic about his technique and over the next seven years he recorded over 8000 successful cases. The Second World War intervened.

Afterwards DJ set up a practice at 53 Wimpole Street, London and continued his use of intravenous anaesthesia. He ran a thriving practice and caught not only the attention of patients wanting oblivion for their dentistry, but also the attention of a group of fascinated medical and dental practitioners. One of these was Dr Henry Mandiwall, a consultant oral surgeon and an accomplished film maker. Together they made a film on venepuncture techniques for general practice. This film was accepted by the British Medical Association and became the first of a series of films detailing DJ's intravenous technique adopted by various teaching bodies.

| 1955 - 1957 |

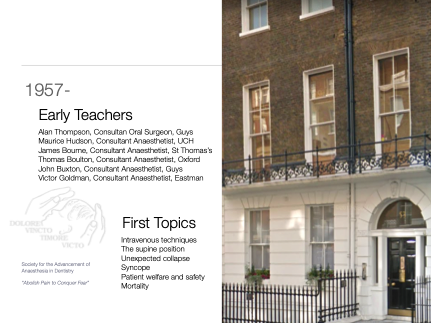

In 1955 DJ started a study club which rapidly grew and by 1957 the Society for the Advancement of Anaesthesia in Dentistry was born. SAAD’s first president was Mr Alan Thompson, a consultant oral surgeon at Guy’s Hospital, London.

Alan Thompson

Alan Thompson

Professor Sir Robert MacIntosh

It was fortuitous that from the start SAAD attracted the interest of the great and the good. The Society's Trust Deed was drawn up by the Lord Chancellor of England together with a future eminent professor of anaesthesia.

It was fortuitous that from the start SAAD attracted the interest of the great and the good. The Society's Trust Deed was drawn up by the Lord Chancellor of England together with a future eminent professor of anaesthesia.

Robert MacIntosh (later Professor Sir Robert MacIntosh) attended meetings because at the time he was providing anaesthesia for dentistry at a dental practice in Mayfair. Although pursuing a fellowship in surgery MacIntosh needed the money dental anaesthesia brought in. Unwittingly SAAD was to become a catalyst in the academic and clinical development of anaesthesia in the UK. MacIntosh gave an anaesthetic in the Mayfair dental practice to Sir William Morris (of early motor car fame and fortune).

Sir William Morris had previously had an unpleasant anaesthetic experience, but MacIntosh's intravenous dental anaesthetic had changed his view. Morris and MacIntosh became friends and subsequently Morris told MacIntosh that Oxford University had approached him with a plan to endow chairs in medicine, surgery, and midwifery.

MacIntosh persuaded Sir William Morris that to endow a chair in anaesthesia would be both innovative and extraordinary. Ultimately Sir William offered Oxford University, four Chairs including anaesthesia and funding of £1 million.

Opposed to the anaesthetic chair, Oxford University declined so Sir William offered the university £2 million to include anaesthesia on a take-it or leave-it basis.

Unable to resist such a magnificent offer, Oxford University established the first department of anaesthetics in Europe.

Sir Robert MacIntosh became the first Professor of Anaesthesia in Europe and Sir William Morris became Lord Nuffield.

Developing a Scientific Basis

| 1957 - 1966 |

From the very first meeting in 1957, SAAD was heavily involved in the use of intravenous anaesthesia and sedation. From the beginning SAAD had a close association with Guy's Hospital, London and that has continued unabated. Early meetings explored the challenges of barbiturate dosage, laryngeal spasm, aspiration, and the supine position for anaesthesia.

The Society’s policy, which placed patient welfare above all else, was outlined by Mr Thompson at a meeting of SAAD in 1958:

(1) We are agreed that we disapprove of the operator acting also as anaesthetist. At the same time we recognise that exceptional circumstances can arise when such a procedure may be justified.

(2) The policy of the Society is for the overall advancement of anaesthesia in dentistry, for the better care and welfare of our patients. To that end, we do not advocate, or are wedded to, any particular technique.

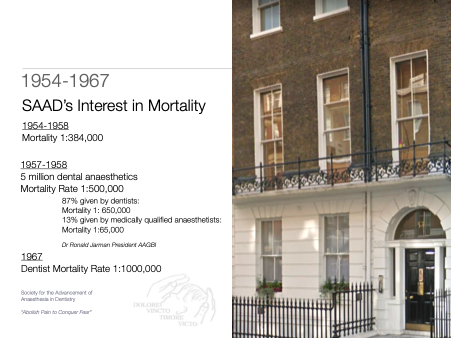

Patient mortality rates were, naturally, an urgent concern. In 1952, a total of 26 deaths out of an estimated 2 million anaesthetic administrations for dentistry purposes were recorded. In 1957 there were 5 deaths, a reduction ‘that it was tempting to ascribe… at least in part, to the increasing use, and safety, of intravenous techniques.’

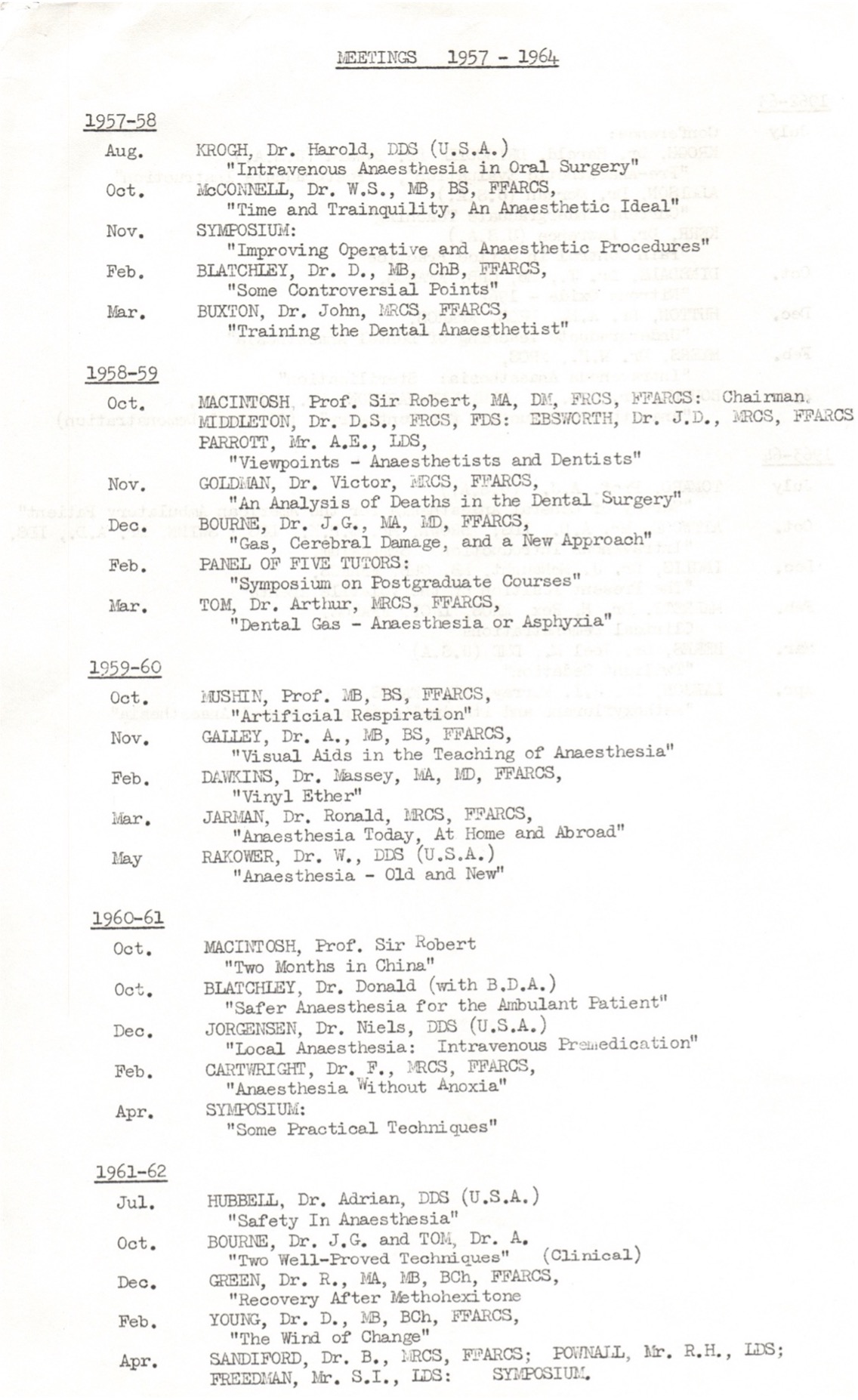

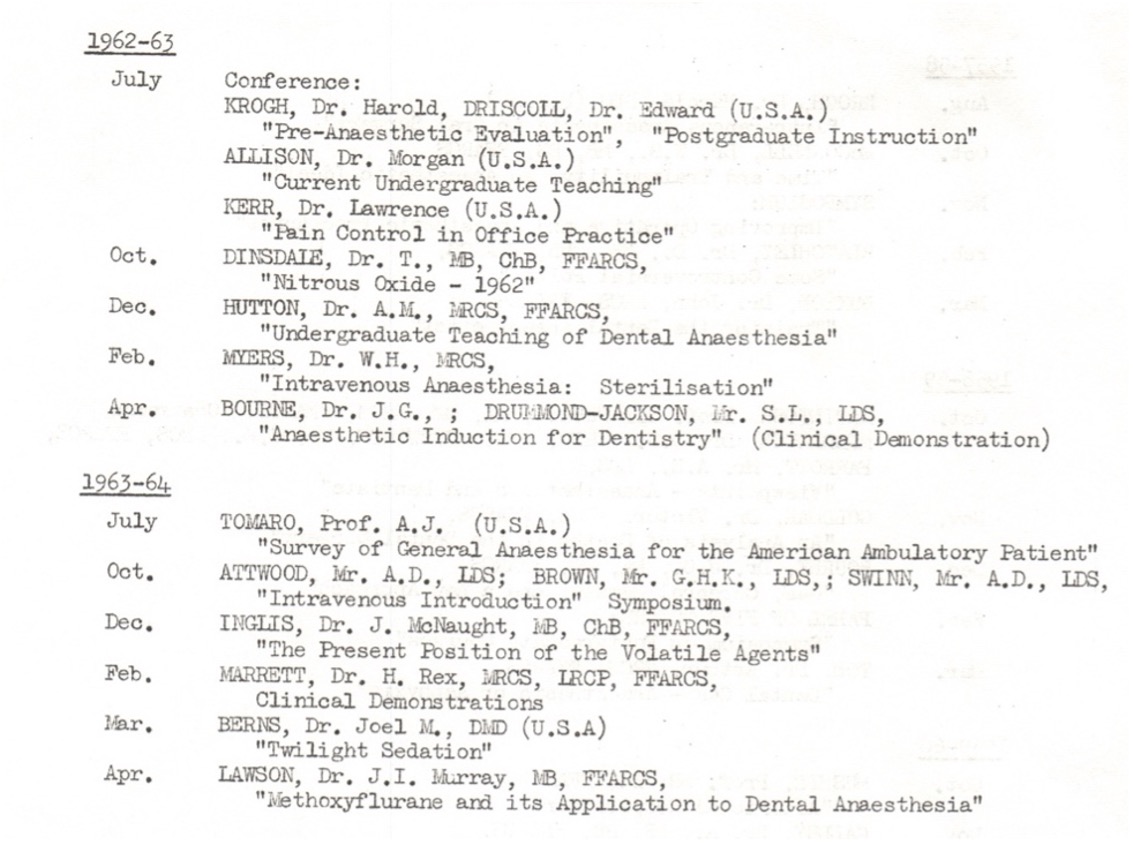

SAAD Diary 1957 - 1966

From the outset SAAD's attitude was clear. The Society had a policy of embracing a range of anaesthetic techniques and formally disapproved of the dental operator also being the anaesthetist. It was agreed that patient welfare was paramount. By 2023 standards, mortality was high with intravenous barbiturates and with these new techniques some career anaesthetists were concerned about selecting the right people to teach how to administer them whether they were doctors or dentists. In the late 1950's it was clear to some that SAAD led the way in the future of intravenous anaesthesia in general and for dentistry at a time when the intravenous route was a minority practice and total intravenous anaesthesia was rare. Meetings were led by Dr John Buxton, a consultant anaesthetist at Guy's Hospital; Dr Morris Hudson, a consultant anaesthetist at University College Hospital; and Dr James Bourne, a consultant anaesthetist at St. Thomas' Hospital, amongst others. Meetings embraced such topics as safety, the causes of syncope and success stories.

Between 1957 and 1960 SAAD was heavily influenced by American and German speakers. There was a particular interest in ultralight anaesthesia and sedation. Intermittent methohexitone sedation and The Jorgensen technique proved to be enlightening for dentists at the time.

In 1959, the technique of intermittent methohexitone anaesthesia was introduced. This was effectively the intravenous drug titrated to effect. As Dr Maurice Hudson, Consultant Anaesthetist and Chairman of SAAD’s sub-Committee on Postgraduate Education, wrote, it was ‘the safest method ever introduced into anaesthetic practice.’ However, even this technique was not entirely free from risk, with the skill of the administrator being of paramount importance.

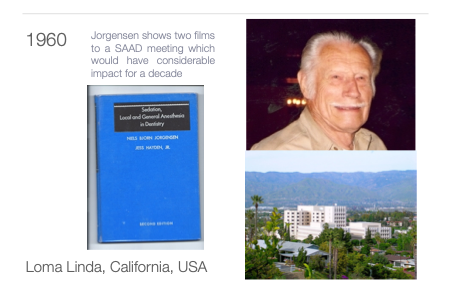

Jorgensen Loma Linda Technique

The ‘Jorgensen technique’, which SAAD began to promulgate from 1960 onwards, owed its name to Professor Neils Bjorn Jorgensen of Loma Linda University, California. Professor Jorgensen visited the Society in December 1960 and outlined the method of intravenous sedation that he had developed. It was not without its problems: effective sedation for a period of less than two hours was difficult to achieve, individual susceptibility varied and could lead to prolonged disorientation or a ‘hangover’ effect of some severity, and – as ever- administration by an inexperienced or heavy-handed practitioner could create its own problems. But it was ‘the first effective step along the road of acceptable dental sedation’, and, given that it allowed for several hours’ work to be undertaken during a single appointment, it was naturally popular.

The first two decades - Update and Jumbo

In 1959 a series of three-day courses were held on general anaesthesia for dentistry. Each course was limited to eight people and took place in the basement of 53 Wimpole Street. The first two days were didactic teaching, and the third day was devoted to clinical demonstrations. As the number of course registrants grew the number of courses went up to eight a year with 24 practitioners on each. In the early 1960’s courses moved to University College London, but the course quickly needed a bigger venue.

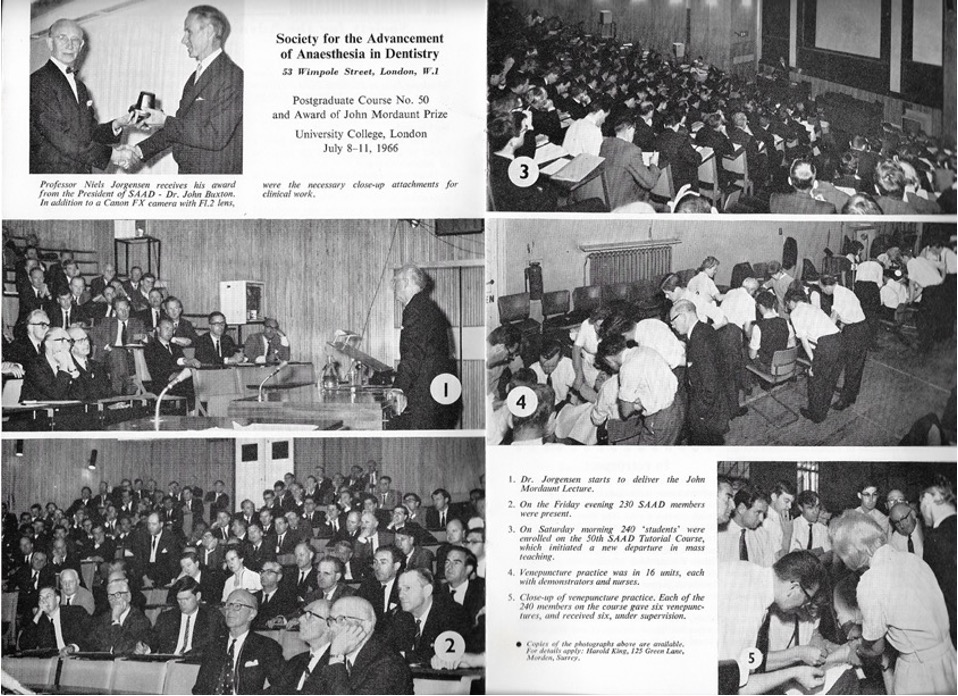

Logistically it became difficult to provide hands on training on an individual basis and practical emphasis was SAAD's modus operandi. This resulted in the development of "table demonstrations" a precursor to the modern rotating seminars of the 1980’s which SAAD still offers today. The Society flourished developing mass training in the so called ‘Jumbo Courses' where up to 240 participants were taught together at University College London.

SAAD Course - July 1996

The first “Jumbo” course took place on 9th July 1966 at University College London, with 240 students undertaking and receiving two cannulations on all three days of the course. Four fully equipped dental surgeries were installed in the College gymnasium and a different technique demonstrated in each. The first demonstrations in this “four-ring circus” covered advanced conservation under Jorgensen sedation; oral surgery under diazepam sedation, and intermittent methohexitone anaesthesia. “The Society makes no attempt to justify such mammoth courses on the basis that they are good as personal tuition,” a subsequent report stated. “However,… there are many hundreds of dental graduates, ill-trained in anaesthetics, who are at present administering traditional methods under conditions which are far from satisfactory. And whatever amount of training they have had, few have been given the basic groundwork of safe practice which is so essential for the welfare of patients under all conditions.”

The drawbacks of the Jorgensen technique of extended sedation, long recovery, and potential hypoxia and hypercapnoea were not inconsiderable. The commercial availability of diazepam as intravenous Valium arrived. In 1968, a SAAD symposium was devoted to the dental uses of the drug, although at the time its makers, Roche, objected to its use outside hospitals. However, its advantages were clear: sedation could be of shorter duration and its effects more controlled, the patient remained co-operative, and the amnesia that followed ‘could be exploited in the fearful patient to promote a return for further treatment without terror.’ The drug’s safety determined, and Roche’s objections notwithstanding, SAAD began to promulgate its use.

From the following year, 1967, participants were formally required “to have experience of the administration of anaesthetics and the handling of emergencies”. Those who did not possess the latter were directed to their local branch of St John Ambulance or the Red Cross. As Peter Sykes observed, this is particularly striking because it was not until 1989 that the General Dental Council decreed that “all dental practitioners and their staff should be competent in basic resuscitation”[1]. Indeed, it was the pressure put on the GDC by SAAD through Peter Sykes and Gerry Holden, both elected members of the GDC, that led to it adopting this stance.

Safety was, as always, SAAD’s governing principle, and by 1967 10% of all UK dentists had attended a SAAD course.

The development of teaching from the beginning to our modern society today traces a record of the challenges of teaching large numbers of doctors and dentists new clinical skills and the provision of safe and comfortable care for patients in constantly changing political circumstances. Some doctors and dentists openly disapproved of SAAD's initiative.

SAAD grew rapidly as did the practice of intravenous anaesthesia in dentistry. By 1967 membership was 2000 and 10% of dental practices in the UK provided intravenous anaesthesia. This rapid spread led to alarm by an increasing number of dentists and anaesthetists.

The Supine Position

Another milestone in the history of SAAD came with the development of the first supine electrically driven dental chair. Until the 1960s in Britain, practitioners traditionally stood behind and bent over their patients, who were seated upright in a chair. To operate the footswitch of the dental drill, the dentists were required to stand on one leg.

SAAD had a long debate about syncope on induction of sedation and the “sit up and beg” traditional dental chair was seen as cumbersome and not fit for purpose for sedated patients.

In 1967, an American dentist, Dr Daryl Beach, visited the Society to expound the virtues of the supine technique (ease, efficiency, and comfort chief amongst them). Beach had designed his own ‘Spaceline’ unit, a flatbed “chair” that incorporated suction, compressed air, and hand instruments into its housing, and it was this that inspired SAAD member and future President Dr Gerry Holden to develop a reclining chair to accommodate SAAD’s intravenous techniques. His ideas, and the demand from ever-increasing numbers of practitioners, proved formative in the design and development of dental units. Importantly, these units recognised the increasing role of dental nurses, who now required their own instruments. Functions were therefore divided or incorporated into special mobile units to best allow both operators to perform their respective duties.

The SAAD-developed chair also converted to a bed by electric power, whilst constantly maintaining the position of the arm for the administration of intravenous drugs. Without this innovation, the treatment of patients in the supine position would not have developed so quickly. It would be ten years until UK teaching institutions widely adopted the supine position.

The Operator-Anaesthetist

| 1971 |

In 1971, a government proposed ban on the operator-anaesthetist in dentistry brought what had been a long-running debate to the fore. This had particular significance for SAAD, since a ban ‘would have effectively abolished the intermittent methohexitone technique on which most of SAAD’s teaching was based, because only rarely was it practicable in general dentistry to obtain the services of a separate anaesthetist; however desirable this was admitted to be. Equally significant was that ‘patients faced being denied a safe and effective pain and anxiety control technique’.

SAAD produced a booklet entitled “Treachery” highlighting politically motivated rather than safety motivated proposed regulatory action.

Peter Sykes commented: Along with The British Dental Association, SAAD took on the Government …… “Treachery” was sent to every Member of Parliament detailing both the sacrifice of basic rights of patients and professional freedom of doctors and dentists and the potential loss of invaluable years of progress in pain control. Members of Parliament agreed - SAAD and the BDA won.

The almost invariable presence of a SAAD Council member on The General Dental Council was a further check and balance when it came to the regulation of anaesthesia, conscious sedation, and resuscitation. Particularly notable in this respect was Dr Gerry Holden (SAAD President 1975-1980), whose 1978 definition of conscious sedation for The General Dental Council was developed with Professor Sir Paul Bramley an oral surgeon at Sheffield University. That definition was adopted by The General Dental Council and is still widely accepted, almost unchanged, today.

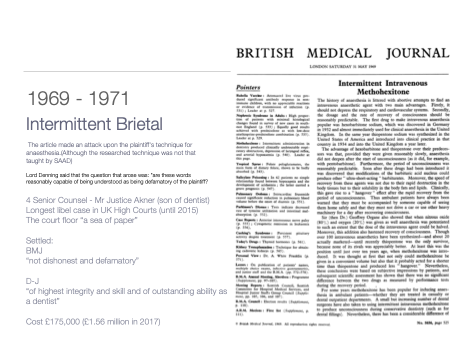

Litigation

SAAD has never avoided the tensions and professional differences between doctors and dentists over who should give what to whom, where and when.

Methohexitone anaesthesia became the centre of a libel case that led to already existing tensions between SAAD and some sections of the medical anaesthetist community coming to a head. In 1969, the British Medical Journal published a paper on the use of intravenous methohexitone for conservative dentistry. The technique, and Drummond-Jackson himself, were both condemned, although the paper’s authors had not followed the technique promulgated by SAAD. When DJ’s request that the BMJ publish a statement of withdrawal was declined, he sued for libel.

What followed was the longest libel action in British legal history for fifty years. Concerned at its length, the presiding Judge, Mr Justice Acker, finally advised that the case be concluded, and that each party ‘exonerate the other from any ulterior motive’.

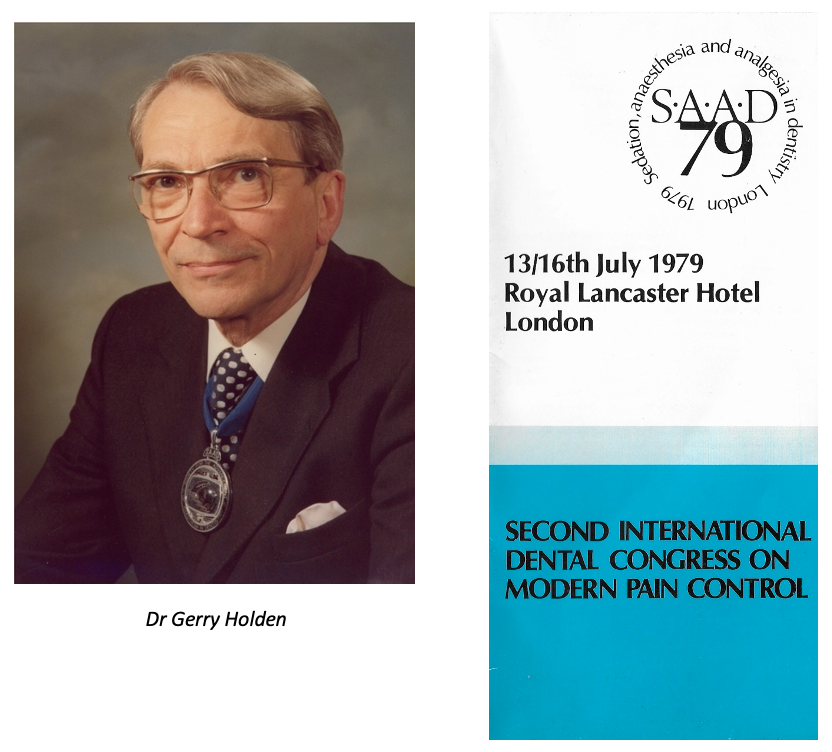

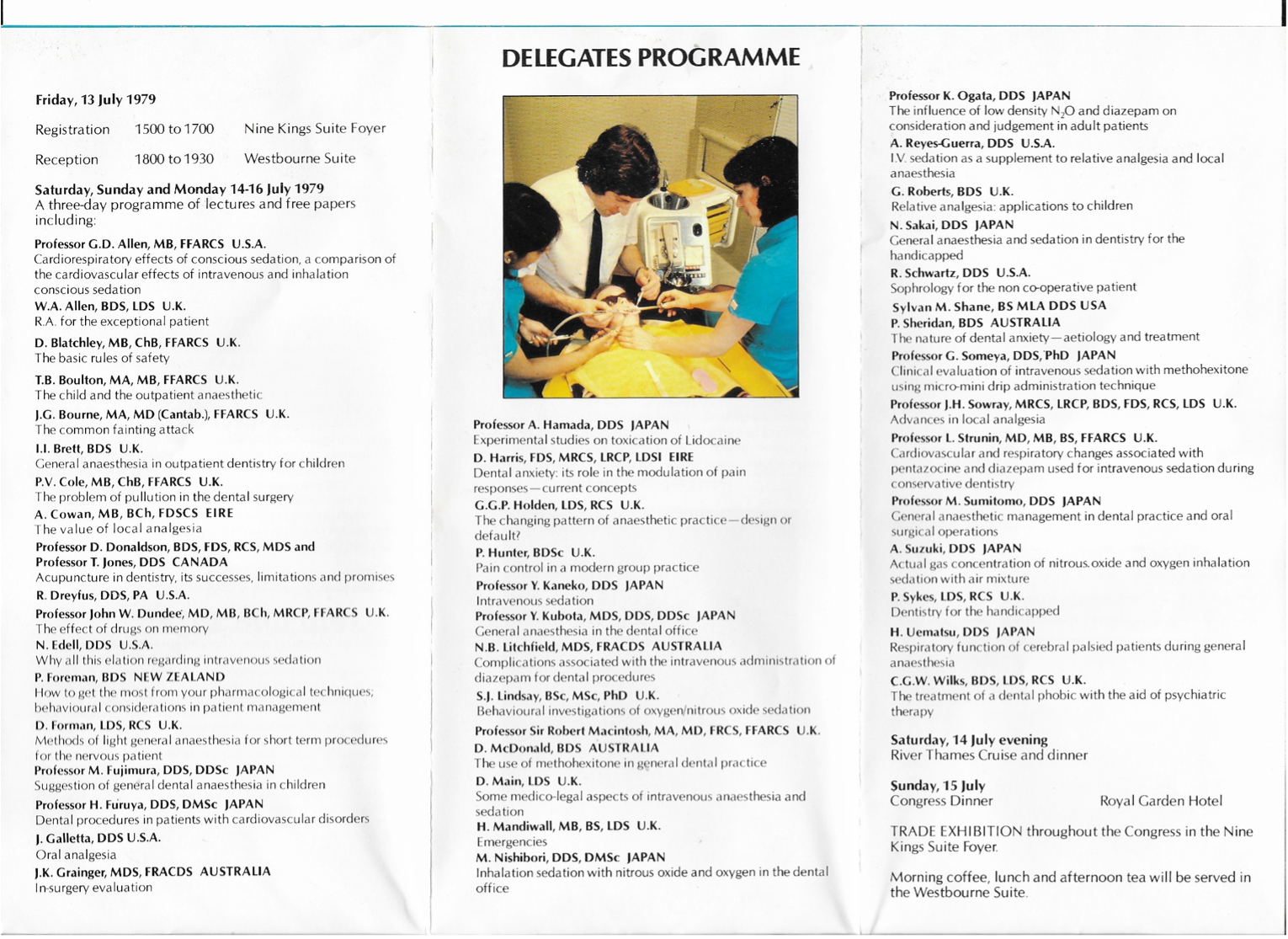

| 1979 |

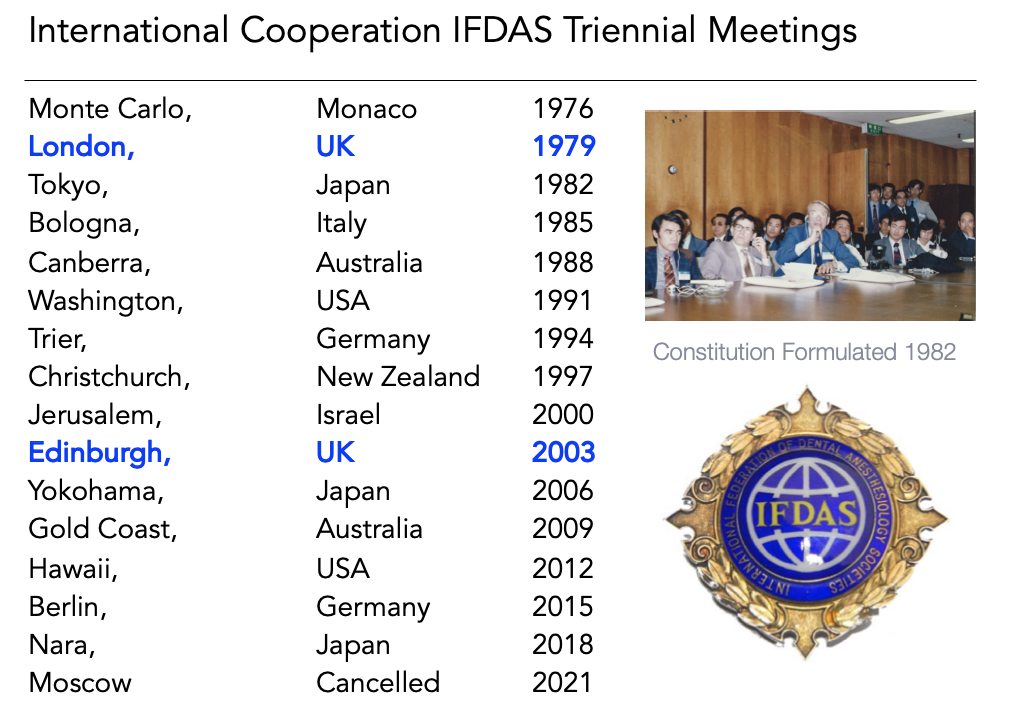

In the 1970’s SAAD had continued interest in developments in other countries and recognised the benefits of international cooperation. The society was keen to establish a formal international organisation. To that end SAAD offered to host an international meeting in London in 1979. Led by Dr Gerry Holden a general practitioner and member of The General Dental Council, who was SAAD’s president at the time. SAAD 79 was a huge success both academically and socially and it set the scene for triennial congresses for decades later. The meeting was considered important enough for the government to host a formal government reception at The Lancaster Hotel, St James’s.

At SAAD 79 the foundations of a formal international federation were conceived which was to be formalised in 1982 at a subsequent congress in Tokyo, The International Federation of Anaesthesiology Societies. IFDAS formed an important conduit for developing and sometimes even harnessing national aspirations particularly in relation to guidance and regulation. The Federation appointed as its first Secretary General, SAAD Council member, Dr Peter Sykes. IFDAS flourished and gained new membership quickly and SAAD continued to fly its flag on the international stage at each of the triennial conferences.

It was clear to most that doctors and dentists had to co-operate and collaborate in the provision of pain and anxiety control for dental patients, but it took a generation to heal the wounds of litigation and both professions viewed each other with some suspicion. Thankfully for SAAD, there were dentists and anaesthetists who saw beyond this narrow issue and Dr Thomas Boulton a consultant anaesthetist from Oxford and Reading and soon after President of The Association of Anaesthetists drew the professions together during his presidency of SAAD in 1980.

The need to teach both sedation and general anaesthesia in a structured way to ensure safety - especially outside of a hospital environment - was becoming increasingly evident to the dental profession. As a result, the medical and dental faculties of the medical royal colleges together with the General Dental Council produced guidance in 1981 with a view to training dentists in general anaesthesia. Several university training/service posts were created and many of these ‘Wylie Trainees’ subsequently went on to SAAD teaching posts, including Dr David Craig and Dr Christopher Holden. At that time some universities were providing a group of young dentists with formal training in general anaesthesia for dentistry during a full time postgraduate in-service training course. Most of these joined SAAD and lacking the baggage of recent history began to renew progress. After the legal case the Society continued to develop by insisting on academic competence, clinical excellence, and appropriate training pathways.

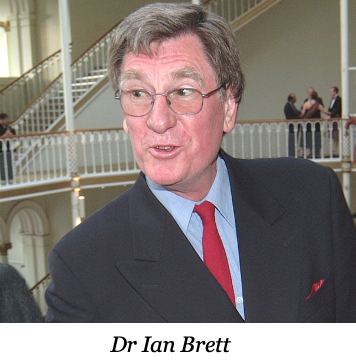

The early 1980s were financially difficult for the Society and but for a new and firm treasurer in Dr Ian Brett SAAD may well not have survived. Ian Brett was a general practitioner in Wimpole Street having taken over Stanley Drummond Jackson’s practice with The Lord Colwyn. Always unassuming Ian Brett coaxed the finances through good investment and wise spending control. This disciplined approach cemented the continuation of teaching until the late 1980’s when one day update courses started. Those courses turned around SAADs financial fortunes for decades to come.

In the 1980's the mainstay of SAAD's training remained two or three day courses with a large practical element. This became known as the "Main Course". During this time SAAD courses moved between the Eastman Dental Hospital, the Whittington Hospital, and the Royal Free Hospital at Hampstead, all necessitated by fluctuating numbers of course participants.

From 1980, SAAD began to promote inhalation sedation (also known as inhalational sedation, Relative Analgesia or RA). This psychosedative technique was imported from the USA and represented a very safe form of mild sedation, relying on maximal suggestion and minimal amounts of nitrous oxide with oxygen. Not to be confused with Entonox it was a hypnotic technique. This proved to be a good alternative for children who were less suited to intravenous techniques. In the mid-1980s, the need to improve the characteristics of intravenous diazepam (Valium) was recognised and a watershed in sedation was about to occur. Although when titrated diazepam produced moderate sedation, its effects were not totally predictable in teenagers who could become tearful and agitated from paroxysmal effects.

| 1984 |

SAAD began to teach the use of intravenous Midazolam (Hypnovel / Versid) in preference to Valium in 1984/1985, with its training becoming more didactic in nature consequently, due to the potency of Midazolam over other benzodiazepines.

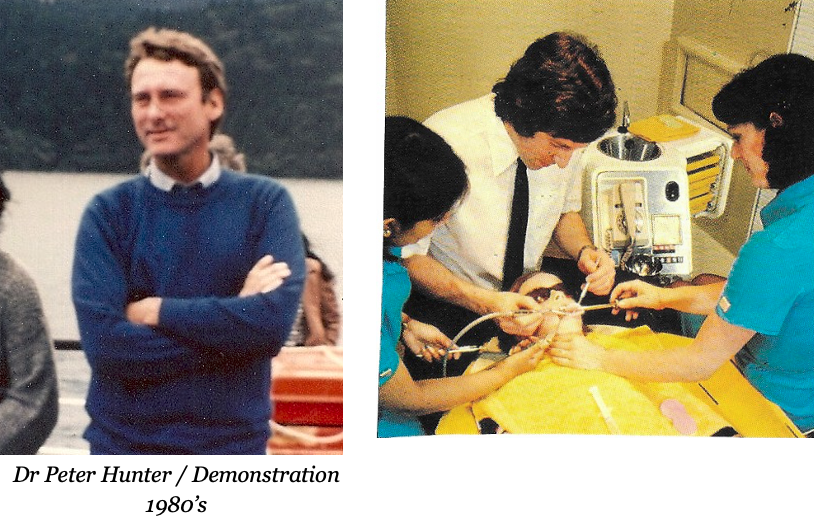

For a time the main course moved to the practice of Dr Peter Hunter in Acton London. Peter Hunter was a forward-thinking Australian dentist whose practice was technologically advanced in equipment, ergonomics and early computerisation.

The facilities necessitated a rotation of small groups experiencing up to eight clinical cases a session. Peter Hunter always charismatic, and never still quickly realised the benefits of this style of training and decided to develop SAAD's seminars.

The course organisers during this time included Dr Brian Swinn a general practitioner from Southampton, and Dr Douglas Stewart who later emigrated to Australia to become an associate professor in dental sedation in Sydney. Following a move to St Bartholomew's Hospital in London, SAAD courses settled there until 2004. A new drive by sequential course director kept “The Main Course” as it had been known contemporaneous and a professional leader. The course developed into “The National Course in Conscious Sedation for Dentistry” reflecting SAAD as the largest postgraduate teaching organisation in this field in the UK.

| 1986 |

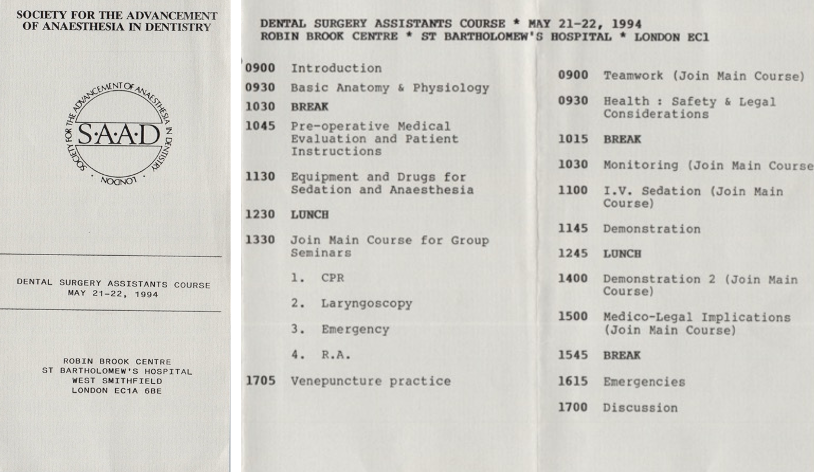

SAAD produced its first guidance document, Guidelines for Physiological Monitoring of Patients during Dental Anaesthesia or Sedation, in 1986. SAAD Council insisted that this should guidance whose goal was achievable by all but underpinned by a minimal standard. A working party was established chaired by Dr Peter Cole a consultant anaesthetist at St Bartholemews hospital, London, and included the youngest and oldest members of council. So it was authored jointly by SAAD dentists and anaesthetists, combining both academic opinion and the opinion of experienced clinicians in primary and secondary care.

| 1987 |

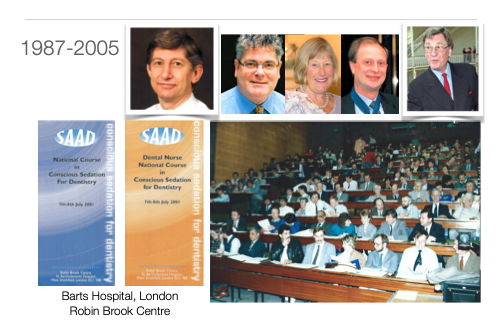

SAAD’s educational mission became the teaching of conscious sedation and life support as opposed to general anaesthesia. Recognising the need for sedation courses to be consistent in content and presentation wherever they were offered, SAAD introduced the National Course in Conscious Sedation for Dentistry in 1987. The format of lectures and live patient cases continued, these being delivered by a growing faculty of dentists, doctors, and anaesthetists. As Christopher Holden comments: “SAAD became synonymous with simple, safe, titrated techniques that kept the patient sedated and comfortable but distant from the oblivion of general anaesthesia.”

1987 also marked the beginning of the first course specifically designed for dental nurses, filling a gap in training identified by Dr Ian Brett. In fact, it had been proposed as early as 1965 that SAAD should offer a training course to dental nurses, but a lack of willing tutors prevented the idea from coming to fruition. The new course was first delivered at 53, Wimpole Street, London, Ian Brett’s practice. Peter Sykes commented that “represented one of the few specialised sources of training in anaesthetic nursing available to the dental nurse.”

During these years attendance at these courses was built as SAAD pushed towards standardised training. The plural nature of the faculty drew on the varied experience of university teachers, general dental practitioners, anaesthetists, and general medical practitioners.

The Society was beginning to develop a more structured training. The courses were relaunched as the National Course in Conscious Sedation for Dentists and Dental Nurses. Both programmes were fully audited continuing professional education programmes offered on a national scale. The new style training and the travelling seminars overcame SAAD's financial difficulties, and the society became financially secure.

Updates and Lifesavers

| 1988 |

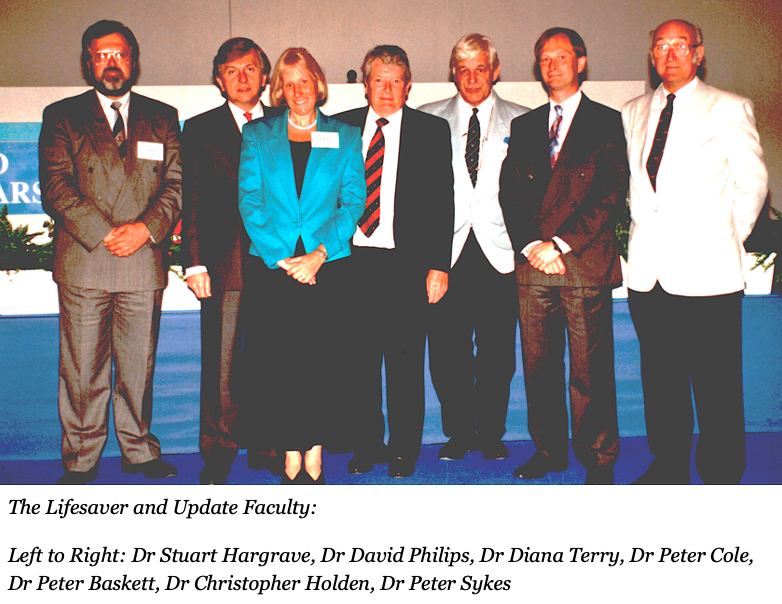

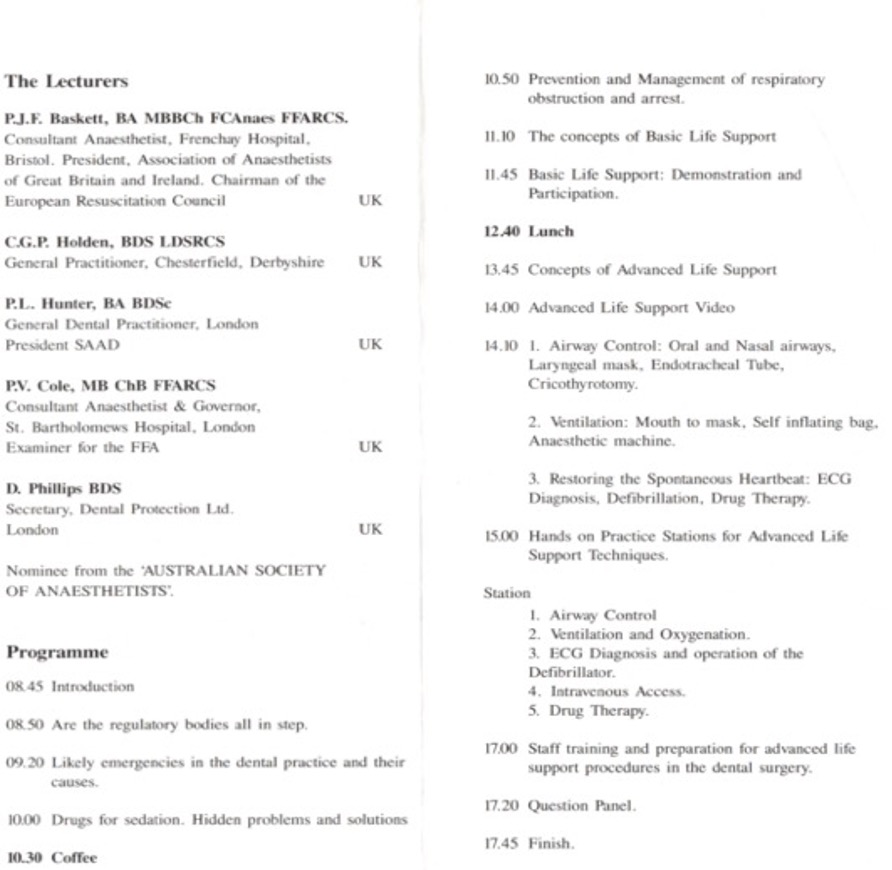

With Dr Peter Hunter's enthusiasm and organisational skills SAAD was one of the first professional groups to develop the "travelling road show" where a diverse group of experts would travel the country to provide the same programme in one or two days. Seminars were titled SAAD Update, Monitoring, Lifesaver I, Lifesaver II, and Update 2. The format was short, punchy lectures followed by rotating practical seminars. The faculty small but dedicated and delivered 59 of these courses.

The Lifesaver courses were amongst the most successful courses run by SAAD. Lifesaver I, the first nationally available CPR course directed at dentists, was attended by over 6000 dentists – more than one third of all UK dentists. Eight years later, in 1996, Lifesaver II was rolled out for the purposes of teaching Advanced Life Support.

SAAD led the way in the late 1980's and early 1990's with resuscitation training for dentists. Although a requirement of the General Dental Council, resuscitation and sedation complication rescue capability was varied both within dentistry and medicine. Training was generally difficult to obtain and largely theoretical. SAAD took up the challenge. This was enthusiastically supported by Dr Peter Baskett a consultant anaesthetist from Bristol who had a background of military anaesthesia and life support. At The Frenchay Hospital, Bristol he trained the first ambulancemen to become what we now know as paramedics in 1969. Peter Baskett became President of The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland and president of the Faculty of Anaesthetists of The Royal College of Surgeons England led the education taught on the seminars.

| 1995 |

Occasionally SAAD also provided short courses with a reduced faculty both in the UK and in several other countries including Germany, France, Belgium, and Zimbabwe amongst others. Wherever it benefitted patient safety SAAD worked with other organisations such as The Association of Resuscitation Training Officers (ARTO) to further training.

| 1996 |

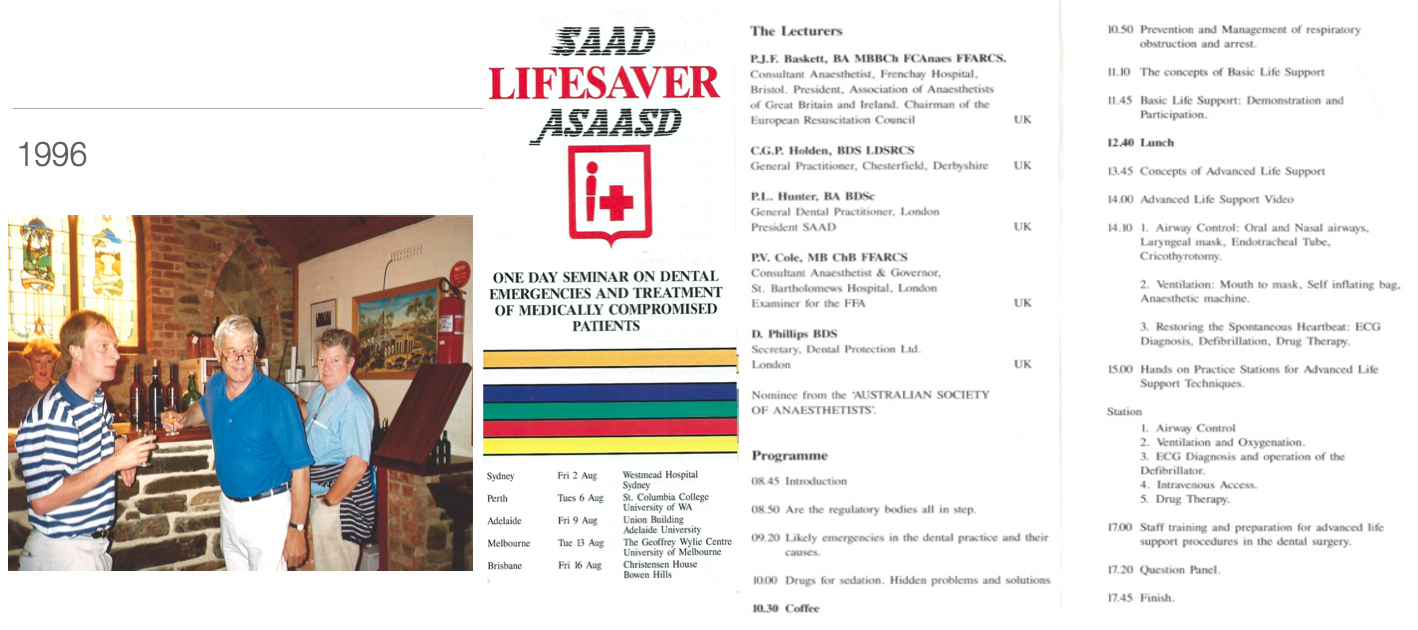

The LifeSaver seminars were so successful that the format of LifeSaver 1 and LifeSaver II was exported in its entirety to Australia. SAAD’s then secretary, the Australian-born Peter Hunter, thought that the course could also be successful in Australia. Although the SAAD council was more than concerned that there might be some resentment of foreigners perceived to be importing “knowledge”, the course was run in all the major cities of the Australian continent in just 17 days. It was a resounding success in participant numbers. SAAD’s hosts in each city were generous and welcoming. As Christopher Holden remembers, “Those of us teaching on this programme spent more time on aeroplanes than teaching.”

| 1997 |

By 1997 SAAD's teaching had transformed from a decade previously and the 40th Anniversary Programme concentrated on new sedative drugs, undergraduate teaching, and the role of dental nurses. The Society was beginning to develop a well-structured training pathway. The courses were relaunched as the National Course in Conscious Sedation for Dentists and Dental Nurses. Both programmes were fully audited continuing professional education programmes offered on a national. During the next five years the society became comfortable reaching out to all specialties within dentistry.

| 1999 |

In 1999 the SAAD “Part 2” course came into being. Developed at Guy’s Hospital by Dr David Craig, its purpose was to help nurses prepare for the National Examining Board for Dental Nurses (NEBDN) Certificate in Dental Sedation Nursing. This finally embedded dental team training as a concept SAAD continues to this day.

As numbers grew it was increasingly challenging to provide teaching heavily reliant on live case presentation a feature of SAAD’s training since inception. The arrival of digital media allowed a streamlining of teaching and less reliance on the logistically difficult live case presentations.

| 2001 |

In 2001, David Craig, who led the Department of Sedation and Special Care Dentistry at Guy’s Hospital, became SAAD’s course director and introduced fundamental changes. These included reducing the National Course from three (labour-intensive) days’ duration to two and a phasing out of its more improvised elements (a portable dental chair constructed by Dr Ian Brett was honourably retired at this time). Live demonstrations of conscious sedation ceased, and procedures were put in place to ensure that the various components of the course – including registration and the provision of equipment and supplies – ran more smoothly.

After many years, SAAD’s courses found a new home in November 2005 when they moved from Barts to Queen Mary University of London. QMUL offered better facilities and the capacity to accommodate ever-growing numbers of participants: in 2001, 70 dentists and 50 dental nurses were booked on the November National Course at Barts; by 2020 enrolment figures were around 100 dentists, 80 nurses and up to 10 therapists/hygienists.

Queen Mary University of London