Please click on the tables and figures to enlarge

An audit of the use of flumazenil for sedation within the Special Care Dentistry Department (CDS Cycle 7) and seven-year comparison

H J Smith BDS MFDS (RCSEd) Pharmacology (BSc)1

R Jaffery BDS MFD RCS Edin PG Dip Cons Sed MSc Rest Dent2

1Dental Core Trainee 2, Special Care Dentistry, Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust

2Senior Dental Officer Special Care Dentistry, Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust

*Correspondence to: Harry J Smith

Email: Harry.smith10@nhs.net

Smith H J, Jaffery R. An audit of the use of flumazenil for sedation within the Special Care Dentistry Department (CDS Cycle 7) and seven-year comparison. SAAD Dig. 2024: 40(1): 33-36

Abstract

Background

Flumazenil is a benzodiazepine antagonist which acts at GABA receptor sites to reverse the sedation effects of midazolam in dental conscious sedation. National Patient Safety Agency Rapid Response Report 2008 identified several cases where patients were being over sedated with midazolam and recommended auditing of flumazenil use as a measure of midazolam oversedation.

Aims

The audit aims to review the number of patients within the Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust’s Community Dental Service who underwent sedation with midazolam and those who required reversal with flumazenil. It also aims to review the record keeping of the justifications given for flumazenil reversal and to ensure compliance with National Patient Safety Agency’s 2008 recommendations.

Methods

Data for patients who underwent intravenous / transmucosal sedation with midazolam between January 2023 and June 2023 were taken from the Community Dental Service’s electronic logbook. Clinical records were then reviewed for documentation of justification.

Results

For cycle seven, (0%) no anxious adult patients required reversal with flumazenil, whereas 5.6% of special care patients (n = 5) required reversal. The majority of reversals cited prolonged recovery as the reason for its use.

Conclusion

The findings demonstrate compliance with National Patient Safety Agency’s recommendations, excellent record keeping and justification of flumazenil use.

Introduction

This year marks 40 years since midazolam was introduced into clinical practice for use as a conscious sedation drug. Forty years on, it remains the most used benzodiazepine drug for intravenous conscious sedation in dentistry.1 Midazolam as a conscious sedation drug is particularly useful within special care dentistry (SCD) where treatment for some patients would not otherwise be possible for a number of reasons. Five years following the introduction of midazolam in conscious sedation practice, flumazenil was introduced as an agent to reverse the conscious sedation effects of midazolam in cases of oversedation, emergency or for other reasons. Flumazenil acts to reverse midazolam by competitive inhibition of its action at benzodiazepine GABA receptor sites.2

Within SCD, the reversal of conscious sedation with midazolam is broadly divided into two main areas of indication: for reasons of patient safety concern, or for prolonged recovery to aid safe discharge.

Despite the usefulness of midazolam as a drug for conscious sedation, the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) received 498 patient safety incidents involving its use in conscious sedation between 2004 and 2008. This led to the development of their rapid response report to highlight those incidents where the doses of midazolam given to patients were inappropriate. The report highlighted the use of flumazenil being relied upon to reverse the effects of patients who have been over sedated with midazolam. The key ‘take home’ message with respect to flumazenil use from the report was that it should be readily available when midazolam is being used, and that the use of flumazenil should be regularly audited as a proxy measure of excessive midazolam dosing.3 Furthermore, the Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry (IACSD) 2020 guidelines recommend that clinicians should be maintaining a log of all sedation cases carried out and of particular note, record reversal of sedation and any untoward events.4

This audit report aims to demonstrate compliance with these NPSA rapid response report recommendations within the SCD team and to compare usage with previous cycles to assess how its use has evolved over time within the service.

Aims

The aims of the audit were:

- To review the usage of midazolam for conscious sedation within the Special Care Dentistry department, the route and doses given

- To explore the level of flumazenil use and if each occasion is adequately justified

- To explore whether the justification for flumazenil use is clearly documented in the patient clinical records

- To compare cycle seven of the audit to the previous six cycles to assess compliance over this time period in addition to monitoring changes in its use.

Materials and method

Inclusion criteria

Patients included in the audit were those who underwent dental treatment under sedation with midazolam within Birmingham Community Healthcare (BCHC) Community Dental Service (CDS). The patient cohort included both special care and anxious adult (AA) / dental phobic (DP) patients.

Audit design

For the last two cycles (cycles 6 and 7), the data for the audit were taken from the special care department’s electronic logbook where all sedations carried out within the service are recorded. For cycles prior to these, the data were taken from controlled drug logbooks of each community dental clinic.

For cycle seven, the data from the electronic logbook were collected retrospectively for the six-month period between January 2023 and June 2023. The logbook data was filtered out to include only patients undergoing conscious sedation with midazolam.

The logbook was used to collect a number of parameters for the purposes of the audit, these were:

- Indication by patient group for sedation (learning disability (LD), physical disability, medically compromised, mental health conditions, dental anxiety, other)

- Midazolam usage: including dose, quantity and route

- Flumazenil usage: Dose quantity median and range, and justification.

Once the flumazenil cases had been identified from the logbook, the patients’ clinical records were then examined to establish if adequate justification was recorded.

Audit standards

The standards for the audit are as follows:

- 100% of cases where flumazenil was used to be recorded in the clinical records with adequate justification

- Reversal rate in the anxious adult sedation group to be less than 1.5%

- Reversal rate in the special care patient cohort to be less than 16%.

The standards for the reversal rate in anxious adult and special care patient groups were determined based upon previous audit data and a recent review of the literature.

Results

Patient cohorts

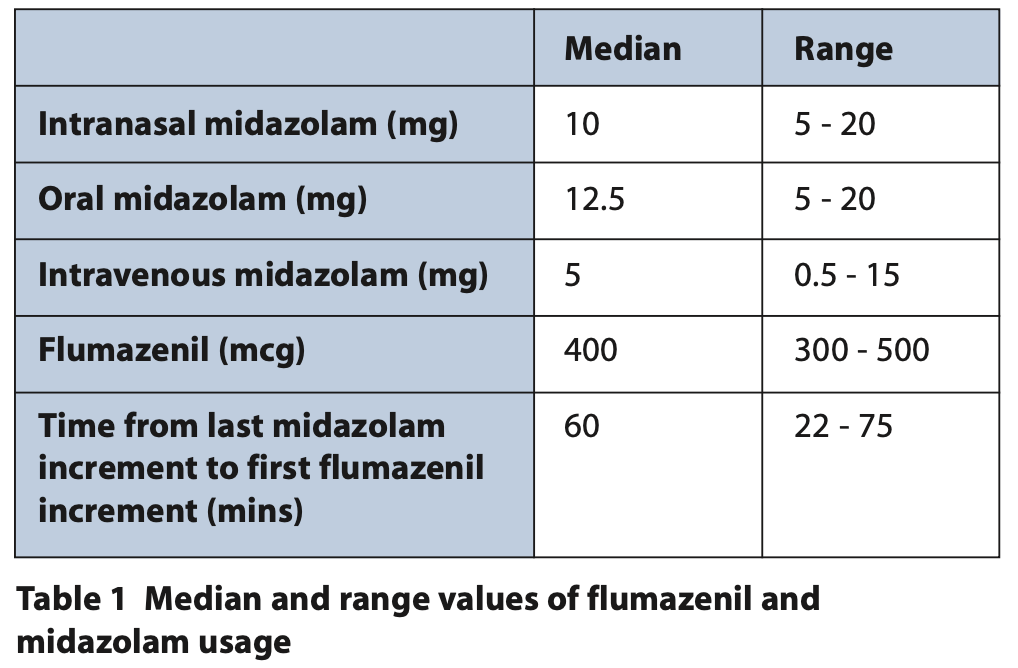

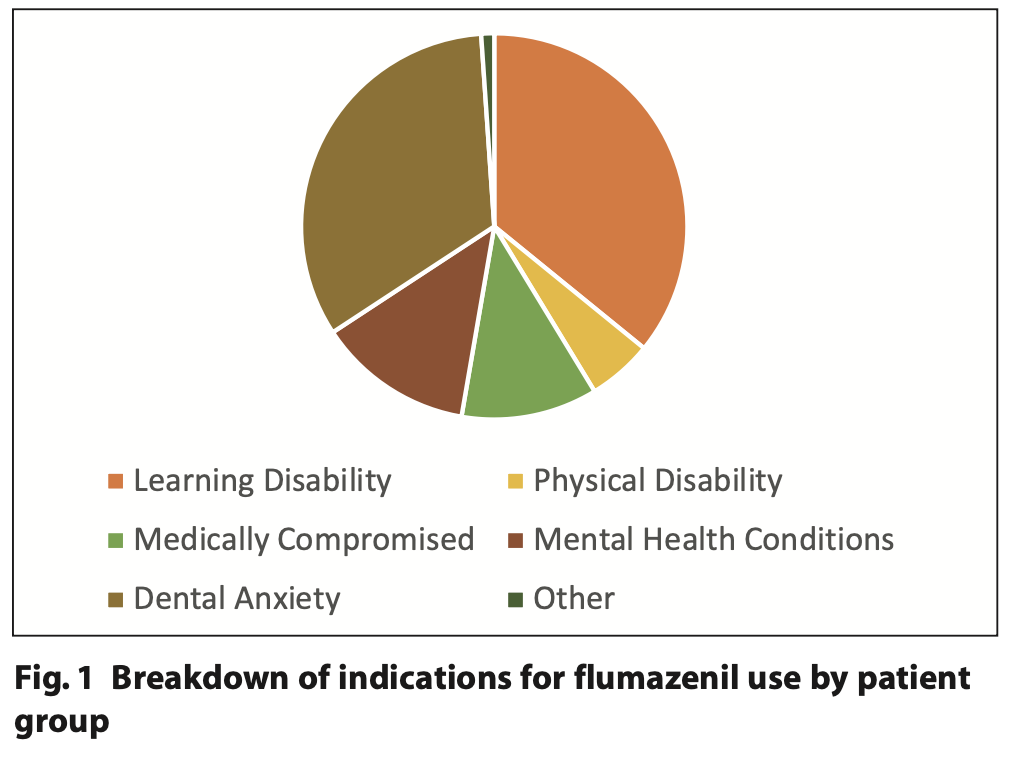

In cycle seven, 130 adult patients underwent conscious sedation using midazolam, this included intravenous, oral and transmucosal / intranasal cases. The specific median and range doses for the different routes of midazolam and flumazenil administration are presented in Table 1. The patient cohort which underwent conscious sedation with midazolam during this time period was broadly divided in to two distinct patient groups: anxious adult (n = 41) and special care patients (n = 89). This was then further subcategorised to demonstrate the range of special care patients treated under conscious sedation (Figure 1).

Flumazenil use justification

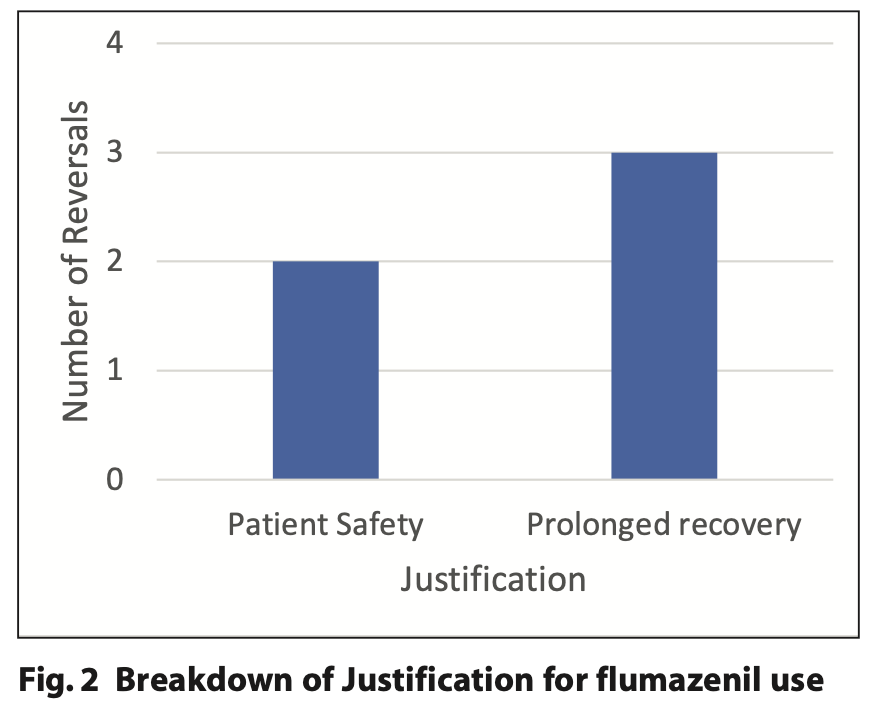

Of the 130 patients who underwent conscious sedation with midazolam, five patients required reversal with flumazenil. Two of the five reversals cited patient safety as the reason, with both referring to the patients becoming agitated and attempting to remove their cannulas. The other three reversals were justified with patients experiencing a prolonged recovery following sedation. All five reversals with flumazenil were within the special care group of patients and therefore none of the anxious adult group required reversal. A summary of the justifications for reversal is illustrated in Figure 2.

Record keeping

For the cases where flumazenil was used, all five cases had clearly documented justifications for its use in the clinical records.

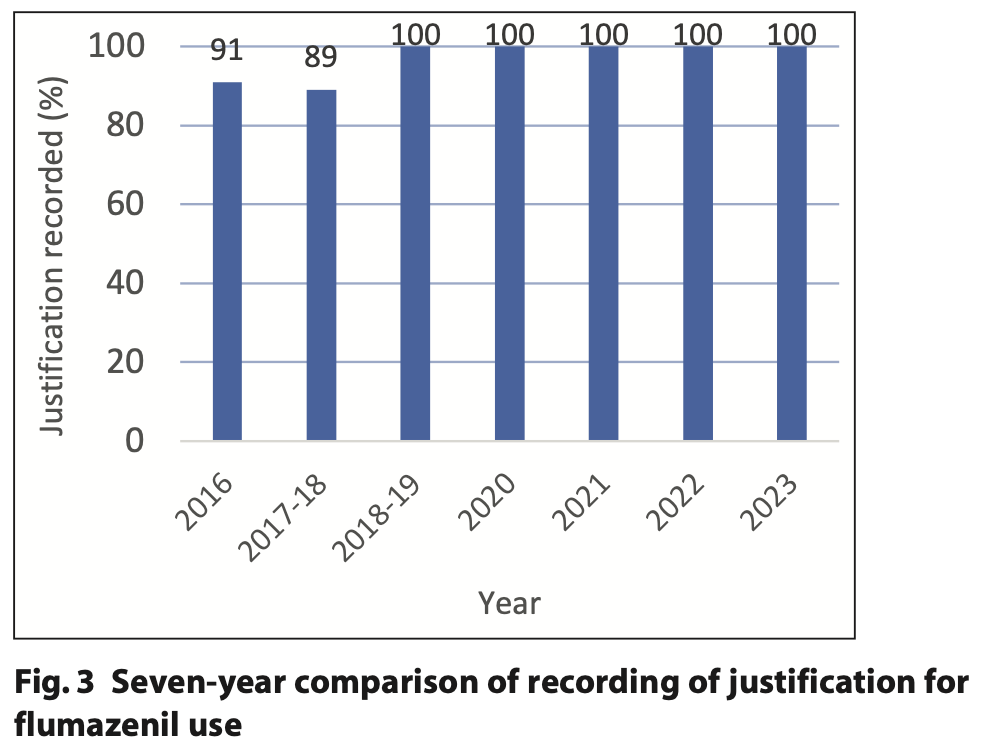

For the last five cycles of this audit, there has been a 100% figure achieved for adequate recording of flumazenil justification in the clinical records. For cycles 1 and 2, the record keeping was achieved at 91% and 89%, respectively. The cited reason for the improvements in the record keeping for flumazenil use is related to the use of the Special Care team’s clinical record template. The record keeping justification is summarised in Figure 3.

Flumazenil use seven-year comparison

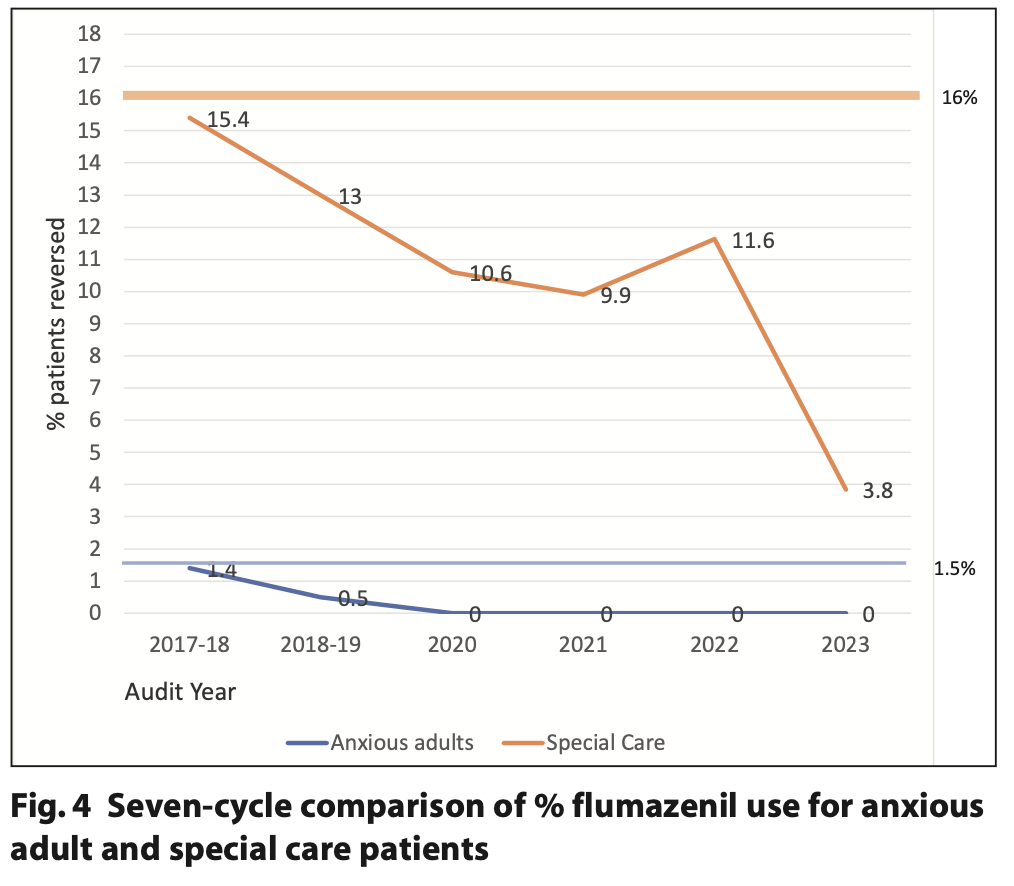

For cycle seven, 5.6% of the patients undergoing sedation with midazolam required reversal in the special care patient group and 0% in the anxious adult group. The reversal rate for anxious adult patients has decreased since 2017 from 1.4% and has remained as no reversals for the last four cycles. Similarly, for the special care group the percentage reversal rate has steadily decreased over time with a 6.0% decrease in reversals from cycle six to cycle seven. The change in flumazenil reversal over the audit cycles is illustrated in Figure 4.

The data for cycle one (2016) is not included in Figure 4 as the data for both anxious adults and special care patients was combined with the reversal rate for that year being 10.2%.

Discussion

One of the significant changes from the last review of this audit published in 2020 is the method of data collection.5 Historically, the data collection has been from the controlled drug books at each clinic, however, for cycles six and seven, these data have been collected from the electronic sedation logbook. The last two cycles have required a combined five hours to gather and analyse the data from the electronic logbook. This represents a significant reduction in clinician time spent working on the audit compared to the findings from the 2020 review which reported a time requirement of 15 hours per audit cycle.5 The significant decrease in time burden is due to the clinician not needing to travel to all community clinics to gather the data. Instead, the clinician can download the data online from the centralised electronic logbook database. Therefore, the new data collection method takes a sixth of the time of the previous method of assessment of controlled drug logbooks, representing better value for money.

Cycle five of the audit compared the accuracy of using the electronic logbook to using the controlled drugs books and identified similar results between the two with some minor discrepancies. There may, therefore, be some merit in periodically verifying the audit data from the electronic logbook with the controlled drug books to ensure clinician compliance with completing the electronic logbook.

The first cycle of the audit (2016) is the only cycle where the reversal rate was combined for both anxious adults and special care patients (10.2%). Due to the great variability in treatment need and reversal rates in these patient cohorts, the decision was made to separate the two patient groups and establish separate reversal rate standards. The standard for the anxious adult patients has remained at 1.5% and is based on previous audit cycle data. Following the separation of the patient groups, there has been a steady decrease in flumazenil reversal noted in the special care group from cycle 2 (15.4%) to cycle 7 (5.6%). There are several factors that may have played a part in this reduction, but one possible reason could be due to changes in the clinical team delivering conscious sedation within the service.

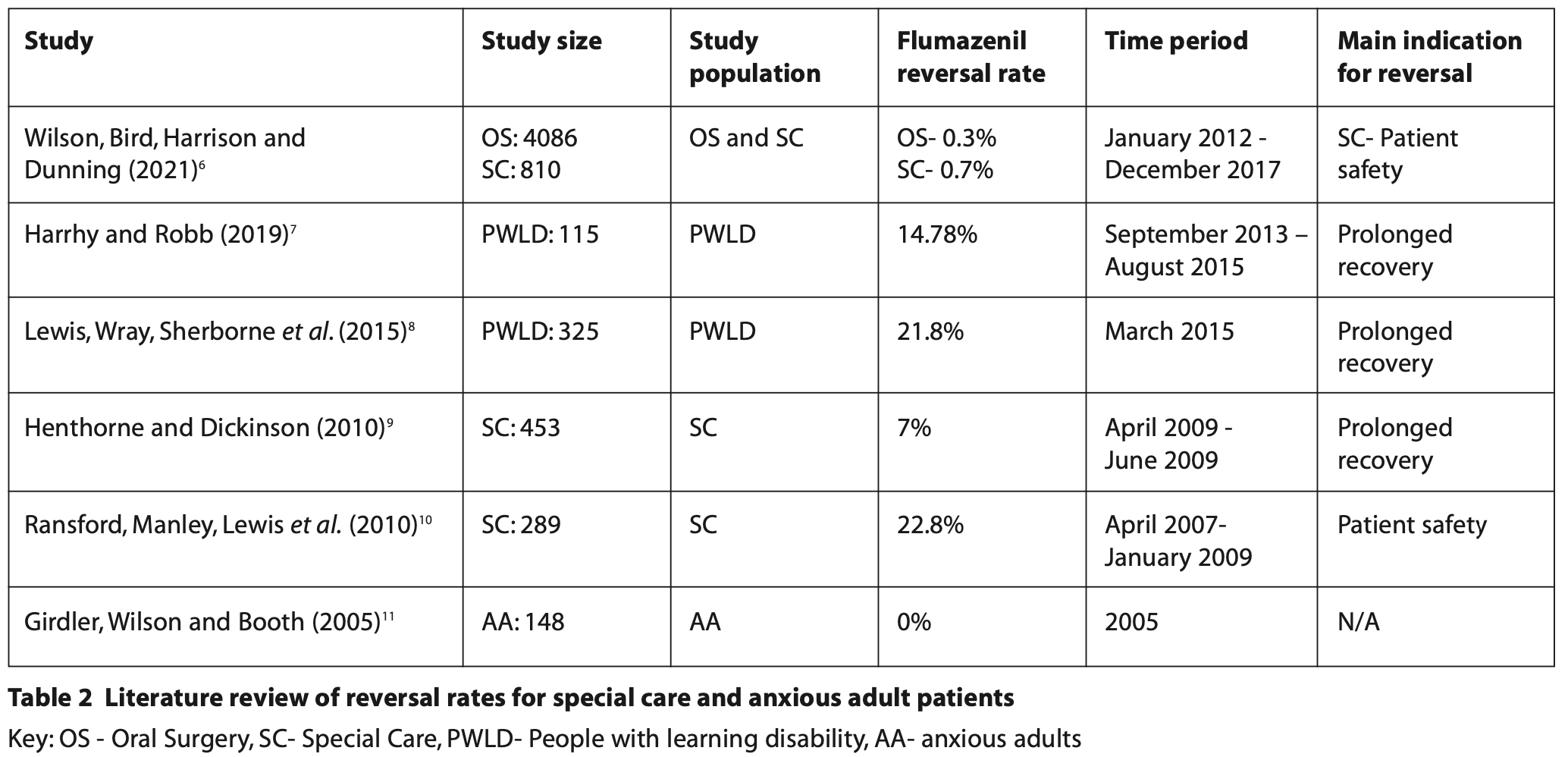

A further change to the most recent audit cycle from previous incarnations is the revision of the flumazenil use standard for special care patients. For the anxious adult cohort, there has been minimal additional data published in the literature on reversal rate in these patients and therefore the decision to maintain this at 1.5% for the most recent cycle is justified. For the special care patients, revision of the standard was carried out following a recent literature search. The reversal rates range varies in the literature from 0.7% to 22.8%6-10 for special care patients. For the previous six cycles, the maximum flumazenil reversal rate was set at 25% with all the audit cycle results falling well below this set standard. Following the literature review (Table 2), the new standard of 16% was established which demonstrates a better representation of reversal rates taken from similar studies. With changes in clinical behaviors and the numbers of patients undergoing sedation with midazolam, the standard for reversal of special care patients may require further revision in the future.

The literature review in Table 2 was conducted using the NHS Knowledge and Library Hub using the search terms ‘flumazenil’ and ‘special care’ to identify relevant UK-based studies. Studies selected within the last 20 years and manual searching of literature were also used to identify additional appropriate studies.

Conclusion

The findings from the most recent audit cycle represent continued good practice from the Special Care team in the use of flumazenil. The reversal rates for both anxious adults and special care patients fall within the set standards. Furthermore, in all the cases where flumazenil was used, its use was fully justified and documented in the patients’ clinical records. With the now streamlined process of data collection, the continued annual re-auditing of the data represents a good use of clinicians’ time to ensure compliance with NSPA 2008’s recommendations for the use of flumazenil.

In addition, the introduction of the Clinical Guide for Dental Anxiety Management in early 2023 could lead to a change in the provision of services to anxious adult patients with more taking up behavioural management or cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) techniques to manage their anxiety as opposed to conscious sedation.12 It therefore highlights the importance of monitoring sedation provision with midazolam and reversal rates in this ever changing landscape of conscious sedation.

Declaration of Interest

No conflict of interest to declare.

References

1. Kapur A and Kapur V. Conscious Sedation in Dentistry. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2018;8: 320-323.

2. Sharbaf Shoar N, Bistas K G and Saadabadi A. Flumazenil. 2023. Online information available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470180/ (accessed June 2023).

3. Rapid Response Report: Reducing risk of overdose with midazolam injection in adults. National Patient Safety Agency, 2008.

4. Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry. Standards for Conscious Sedation in the Provision of Dental Care: The dental faculties of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons and the Royal College of Anaesthetists, 2020.

5. Houlston E and Clark R. A multiple cycle audit of flumazenil use in community dentistry with a review of value of such audits. SAAD Digest 2020; 36: 30-34.

6. Wilson C L, Bird J, Harrison S D and Dunning N A. Audit of flumazenil use in special care and oral surgery sedation services. Br Dent J 2021. Online information available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-021-3001-4 (accessed June 2023).

7. Harrhy C R and Robb N D. The use of flumazenil in a community dental service – a service evaluation. SAAD Digest 2019; 35.

8. Lewis D A, Wray L J, Sherborne M K et al. The use of flumazenil for adults with learning disabilities undergoing conscious sedation with midazolam for dental treatment: a multicentre prospective audit. J Disabil. Oral Health 2015; 16: 33-37.

9. Henthorn K M and Dickinson C. The use of flumazenil after midazolam-induced conscious sedation. Br Dent J 2010; 209: E18.

10. Ransford N J, Manley M C G, Lewis D A et al. Intranasal/intravenous sedation for the dental care of adults with severe disabilities: a multicentre prospective audit. Br Dent J 2010; 208: 565–569.

11. Girdler N M, Wilson K E and Booth E J. A prospective study of complications and outcomes associated with conscious sedation for the anxious dental patient. J Disabil. Oral Health 2005; 6/1: 24-30.

12. NHS England. Clinical guide for dental anxiety management. 2023. Online information available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/clinical-guide-for-dental-anxiety-management/ (accessed June 2023).