Please click on the tables and figures to enlarge

A review of the awareness and use of airway assessment techniques in conscious sedation in dentistry

M. Ismail*1

S. Nayani-Low2

B. Kerr2

1ST2 in Special Care Dentistry, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, Great Maze Pond, London SE1 9RT

2Consultant in Special Care Dentistry, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, Great Maze Pond, London SE1 9RT

*Correspondence to: Dr Maryam Ismail

Email: Maryam.ismail@gstt.nhs.uk

Ismail M, Nayani-Low S, Kerr B. A review of the awareness and use of airway assessment techniques in conscious sedation in dentistry. SAAD Dig. 2024: 40(1): 9-14

Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the the understanding, proficiency, confidence with and anticipated usefulness of common airway assessment techniques when assessing patients for provision of conscious sedation amongst dental sedationists.

Methods

An online questionnaire was sent to conscious sedation providers in dentistry in the UK. The questionnaire explored current practice, use and documentation of airway assessment and information regarding airway-related complications experienced.

Results

254 responses were received. 67% routinely carried out airway assessment whilst 40% documented this finding most or all the time. The average number of airway assessment techniques known was 3.96 of 8. The most common technique known was measurement of mouth opening (71%); this was the most used, the technique participants were most confident using, and the technique found to be the most useful. 11% had experienced an incident where obstruction or hypoxia had occurred where an airway assessment could have predicted this.

Conclusions

The need for airway assessment is recognised within current guidelines and this study illustrates dentists do routinely carry out airway assessment. The technique used, documentation and level of training are varied. A uniform approach to training and the use of a formalised tool may help improve application of airway assessment in sedation in dentistry.

Introduction

The provision of adequate anxiety control is an integral part of the practice of dentistry as an estimated 11.6% of adults in the UK suffer from a high level of dental anxiety.1 Conscious sedation is widely used by dental practitioners to manage dental anxiety and allow for unpleasant or painful procedures to be carried out without the requirement of a general anaesthetic. Conscious sedation is defined as:

‘A technique in which the use of a drug or drugs produces a state of depression of the central nervous system enabling treatment to be carried out, but during which verbal contact with the patient is maintained throughout the period of sedation. The drugs and techniques used to provide conscious sedation for dental treatment should carry a margin of safety wide enough to render loss of consciousness unlikely.’ 2

Intravenous (IV) midazolam is the main IV sedation agent titrated to effect and used for adults in the UK.3,4 This is typically provided with the dentist acting as an operator-sedationist, providing both the sedation and dental treatment. The side effects of midazolam include respiratory depression and airway obstruction which can

rapidly lead to hypoxia if not managed appropriately.5 Conscious sedation in dentistry has an excellent safety record in the UK and there is limited published literature available which reports on airway-related complications during the provision of conscious sedation in dentistry.7,8,9

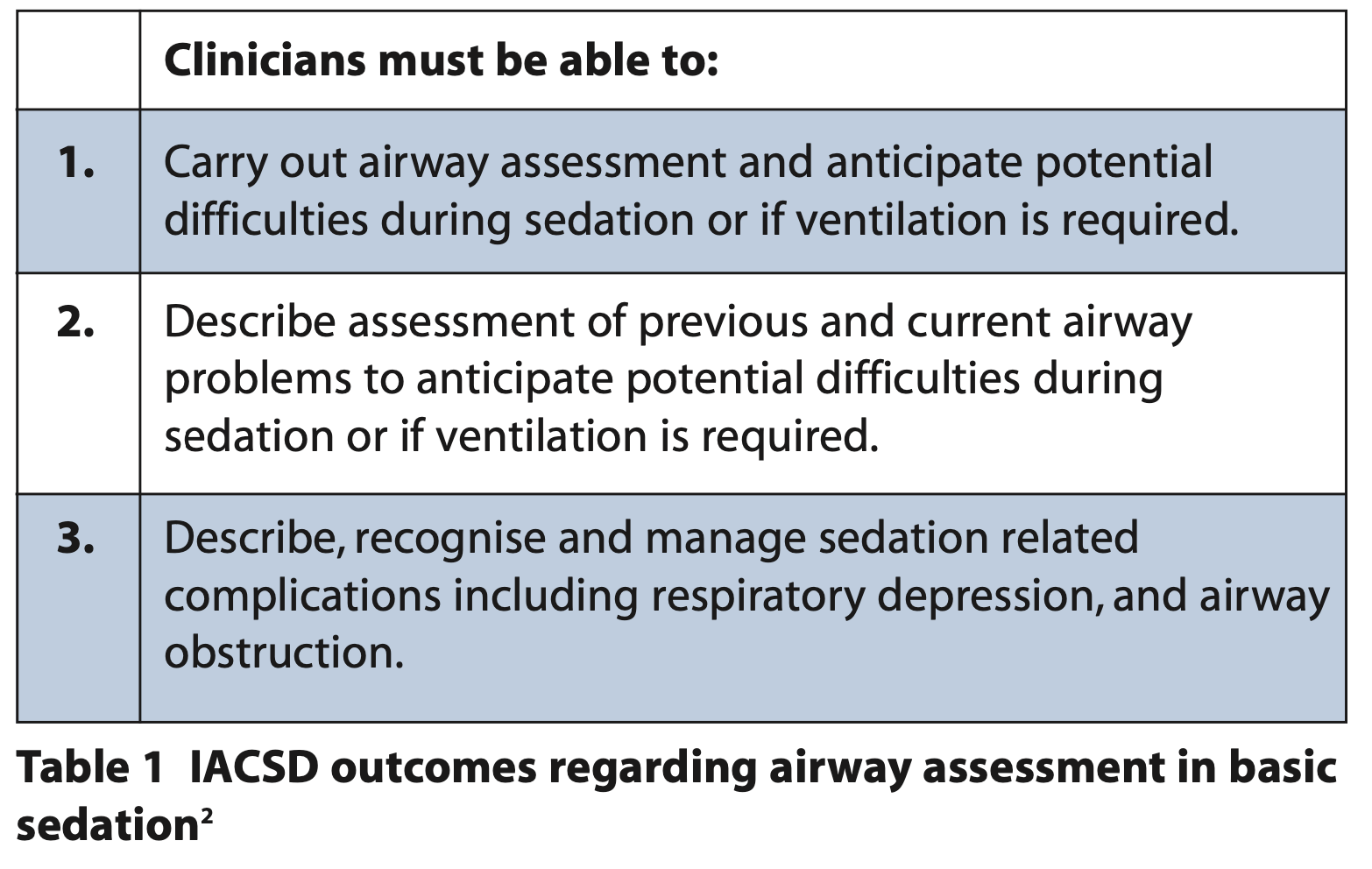

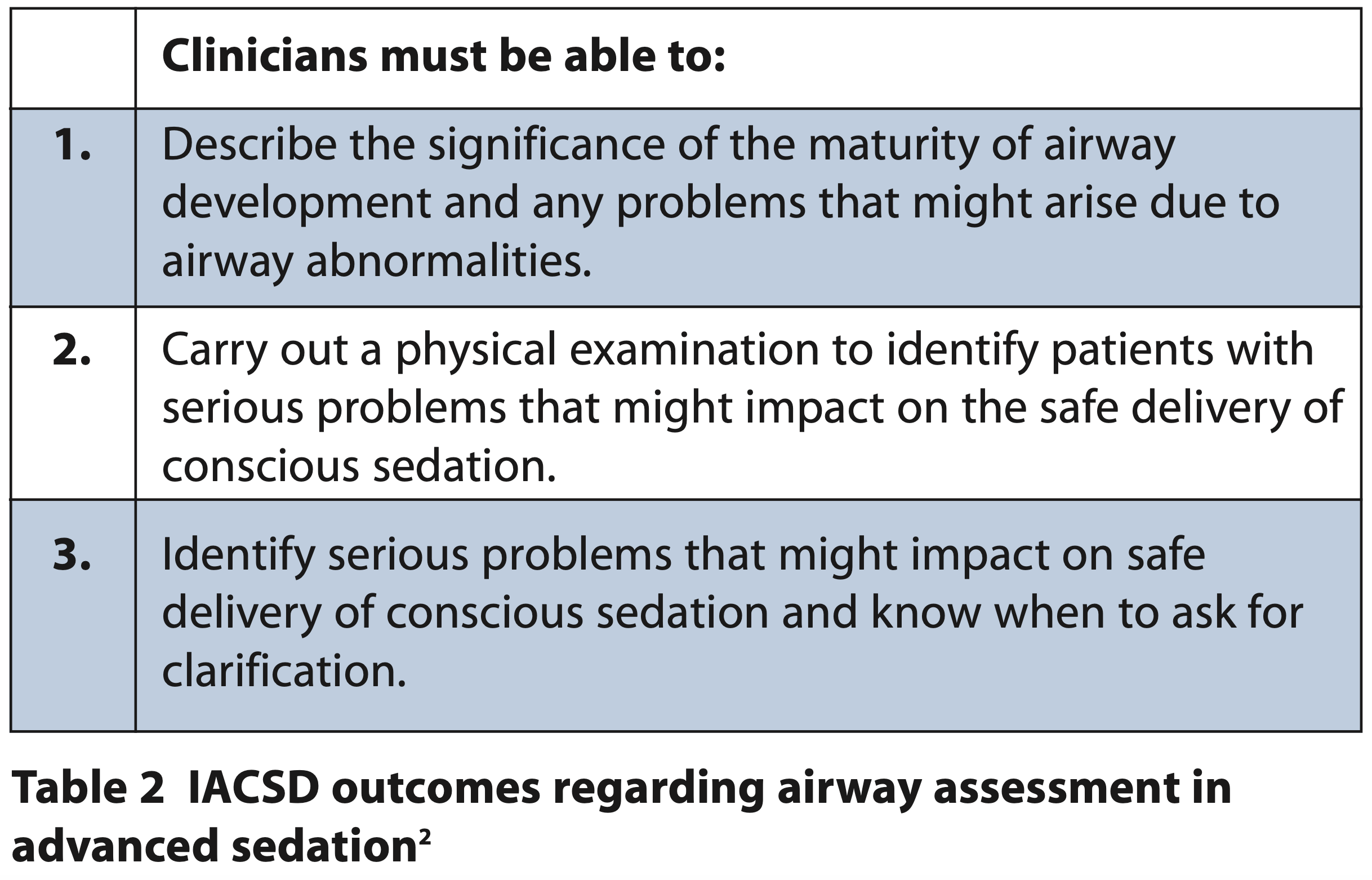

The current guidelines for conscious sedation in dentistry within the UK are The Standards for Conscious Sedation in the Provision of Dental Care: Report of the Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry (IACSD guidelines).2 Within these guidelines, the risk of airway-related complications such as hypoxia and respiratory depression are discussed and state that clinicians providing sedation must be able to ‘…carry out airway assessment and anticipate potential difficulties during sedation or if ventilation is required.’2 This is reinforced across other UK guidelines regarding conscious sedation,10,11 however, none of these guidelines specify how airway assessment should be carried out. Tables 1 and 2 outline the guidance within the IACSD guidelines regarding airway assessment in basic and advanced sedation.2

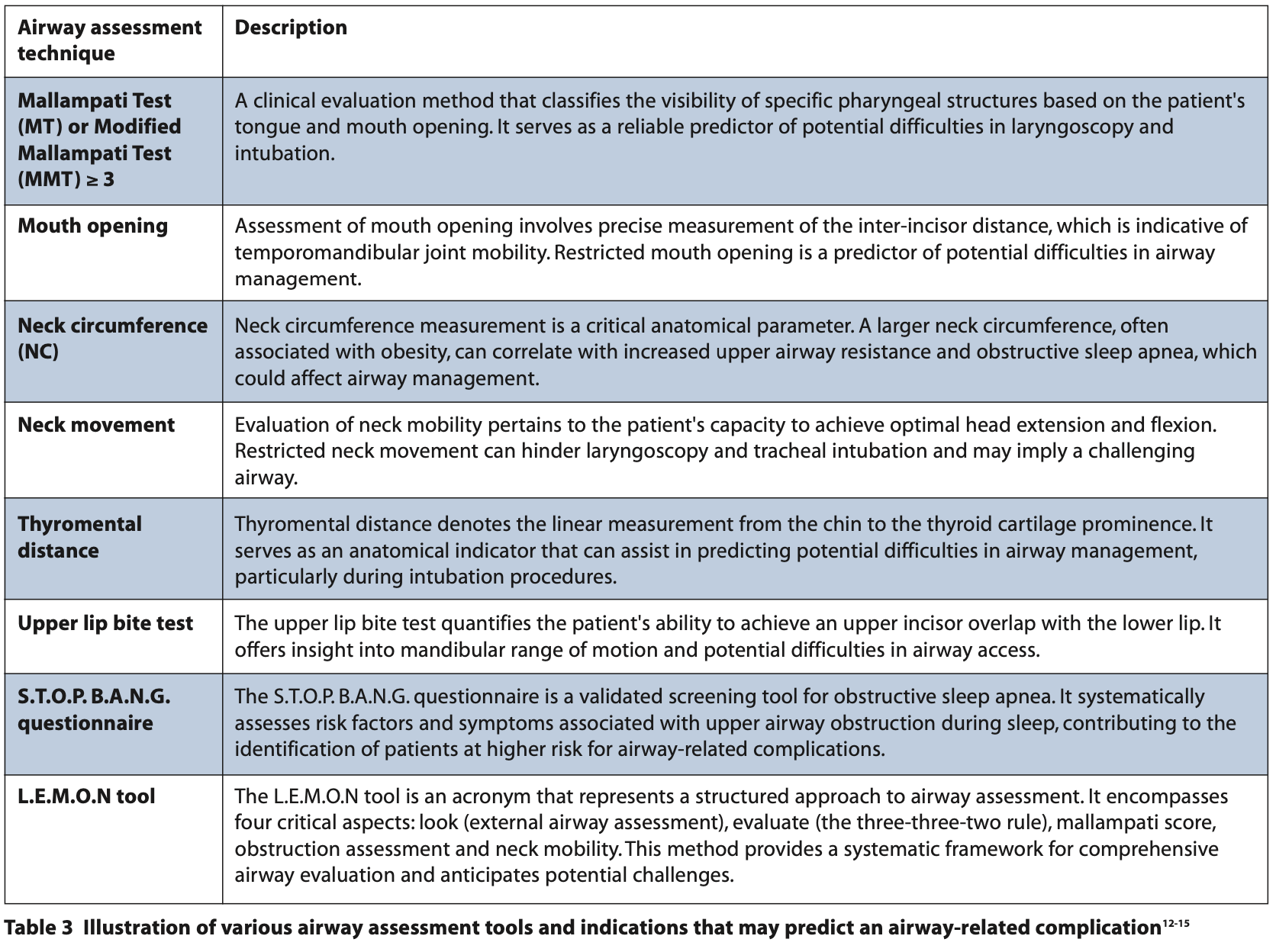

There is limited research available exploring airway assessment techniques which may predict airway-related complications in conscious sedation in dentistry, as the literature often focuses on general anaesthesia or deep sedation where airway-related complications are more frequent. In anaesthetics, there are a number of airway assessment techniques and indications that may allow the clinician to predict difficulty during intubation. Common examples are outlined in Table 3.12-15

It is important for us to recognise that, with an ageing population, we will be treating those with increasing co-morbidities who are at higher risk of conscious sedation-related complications. Identifying patients at risk of airway complications should be part of routine care and will be increasingly relevant in the future as we encounter more challenging treatments.

Aim

To evaluate the the understanding, proficiency, confidence with and anticipated usefulness of common airway assessment techniques when assessing patients for provision of conscious sedation amongst dental sedationists.

Methodology

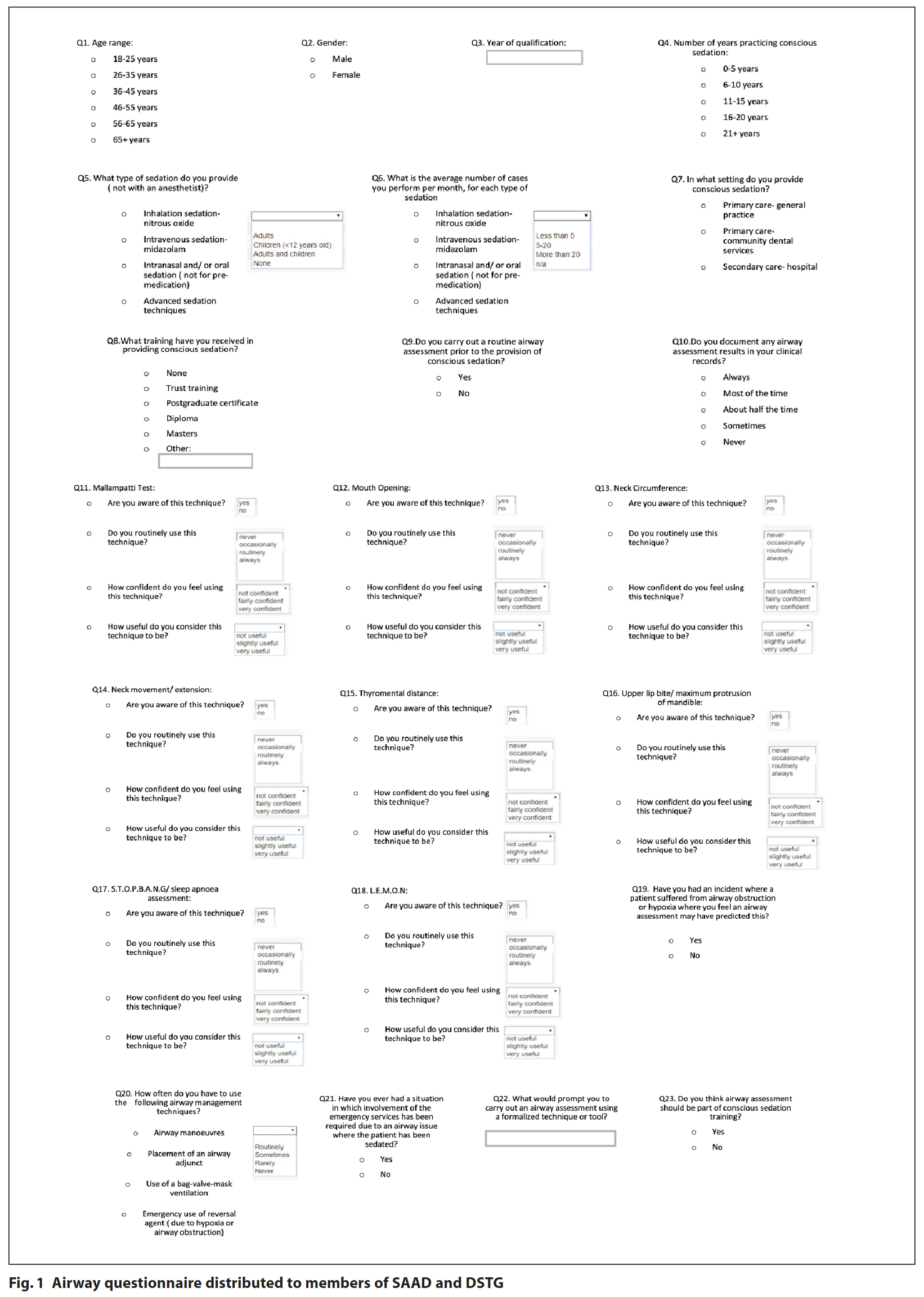

An online, anonymous, cross sectional survey was distributed to members of the Society for the Advancement of Anaesthesia in Dentistry (SAAD) and the Dental Sedation Teachers Group (DSTG). Ethical approval was sought and granted by King’s College London Ethics Committee. The questionnaire explored:

- Current conscious sedation practice

- Awareness, use and confidence in using eight common airway assessment techniques

- Documentation of airway assessment

- Experience of airway-related complications when providing conscious sedation

- Prompts which would encourage participants to carry out airway assessment.

The questionnaire is shown in Figure 1. Responses were collected over a period of seven weeks, with a reminder sent out at five weeks. The data was then collated and exported for analysis with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS).

Results

Airway assessment in current practice

254 out of 1,881 complete responses were received (response rate = 13.5%). 67% of respondants routinely carried out formal airway assessments and 40% documented this finding most or all the time.

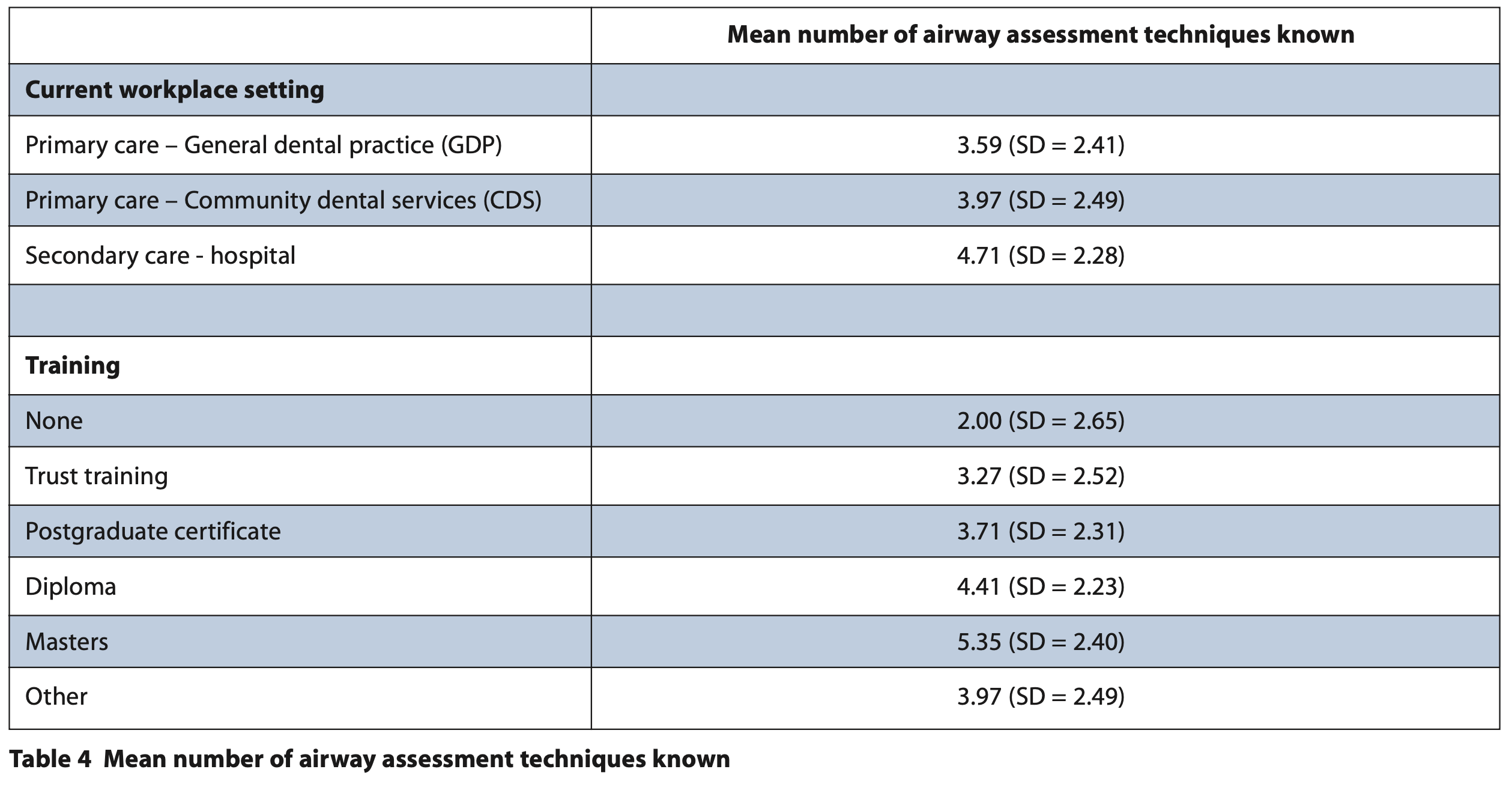

The mean number of airway assessment techniques known by participants was 3.96 (SD = 2.49). Table 4 illustrates the mean number of tests known by participants based on their current workplace setting and training.

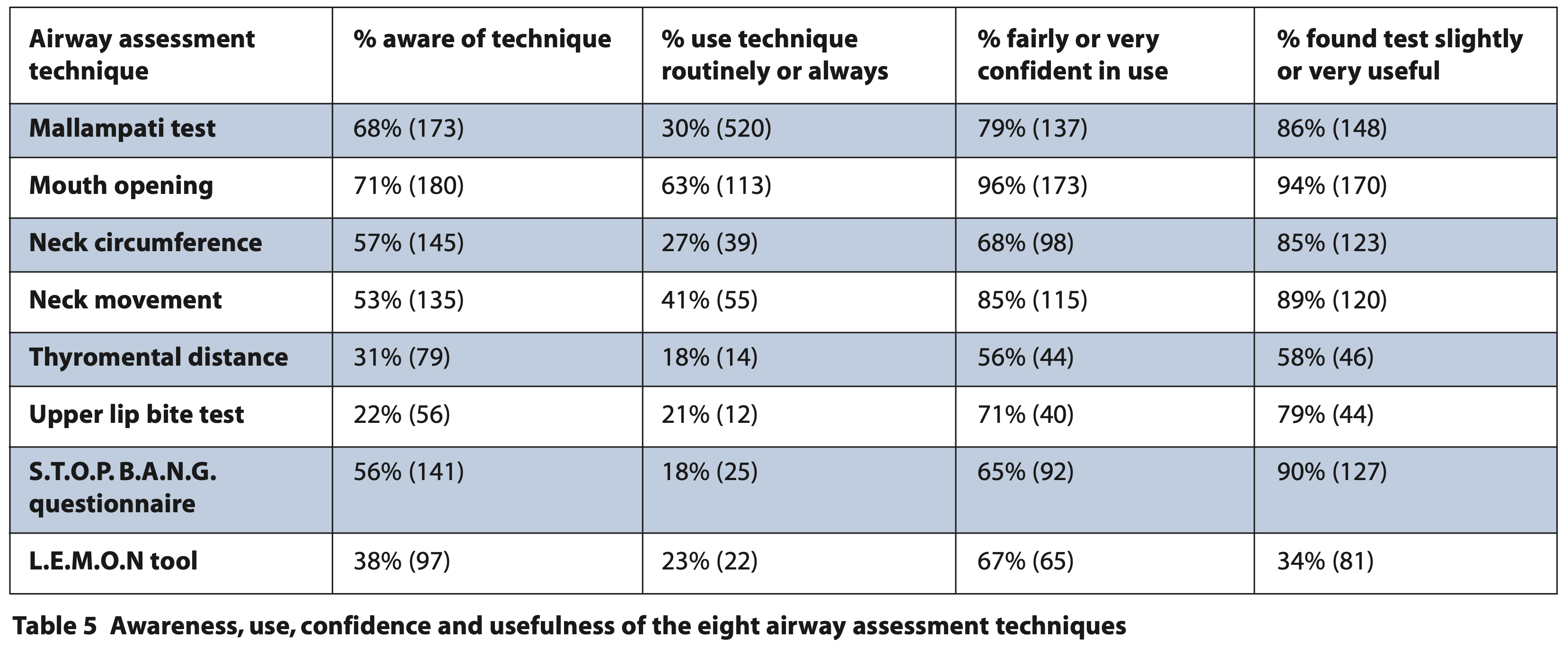

The most common technique known was measurement of mouth opening (71%). This was the most used, the technique participants were most confident using and the technique found to be the most useful, as can be seen in Table 5.

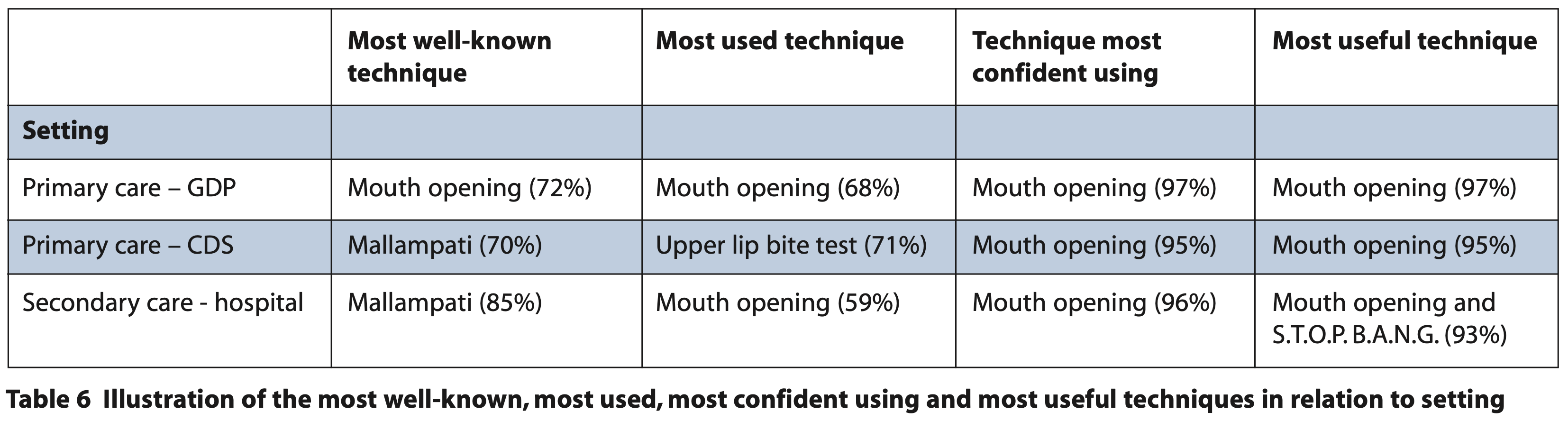

Table 6 illustrates the most well known, most used, most confident using and most useful techniques in relation to the setting participants worked in. These results were calculated as a percentage of the people that knew that specific assessment technique.

Participants who routinely carried out and documented airway assessment were aware of more airway assessment techniques (p <0.001), and those who did carry out an assessment routinely tended to be more confident in their use (p <0.001 – 0.006).

Airway-related complications

11% (n = 28) had experienced an incident where obstruction or hypoxia had occurred where an airway assessment could have predicted this. 2% of participants (n = 6) reported an incident where emergency services were required due to an airway-related complication.

Training in airway assessment and future development of airway assessment tools

94% of participants (n = 240) felt that airway assessment should be part of conscious sedation training. Indicators that would prompt participants to use a formalised airway assessment technique included: clinical indication (39%), clinical history (17%), standardised protocol (13%) and guidelines (12%).

Discussion

The two largest dental conscious sedation societies, SAAD and DSTG, were contacted and asked to share the questionnaire with their members. This was the most comprehensive way in which potential participants could be contacted as there are currently no registers or databases of dental sedation providers in the UK. As a result, clinicians practising conscious sedation in dentistry who are not members of these societies were not invited to participate in the questionnaire, which may have resulted in our sample being unrepresentative of current practice. Additionally, it's worth considering that a subset of clinicians are affiliated with both societies. Consequently, the 13.5% response rate will not be an accurate representation, as some individuals will have received the questionnaire twice. Despite this, the response rate of 13.5% is poor and therefore may not be representative of current practice.

Current guidance states that airway assessment must be carried out prior to the provision of sedation, however, only 67% reported undertaking a formal assessment and 40% stated that they documented their findings. The reasons that clinicians did not carry out formal airway assessments were not explored in this study, and further research in to this would be recommended. One reason for this may be that many of the airway assessment techniques are designed to assess the airway prior to intubation and not for the prevention of airway-related complications prior to conscious sedation.

The mean number of airway assessment techniques participants were aware of was 3.96 (SD = 2.49) of 8. Those who worked in secondary care were found to be aware of the most techniques (mean = 4.71, SD = 2.28), and general dental practitioners were aware of the least (mean = 3.59, SD = 2.41). This is likely to be due to those who provide conscious sedation in secondary care tend to have undertaken more training than those in general dental practice (P <0.033).

Overall, the most well-known airway assessment technique in this study was mouth opening (71%). This was also the most used technique, the technique participants felt most confident using and the technique participants felt was most useful. This may be because mouth opening is a simple, quick to use technique that is naturally incorporated into the patient assessment during a standard dental examination. Therefore, it is a technique that many dentists will have been aware of prior to providing sedation, and it is unsurprising that dentists feel the most confident using this technique in comparison to other techniques.

When comparing the tests known with the setting the participants provided conscious sedation in, we found that mouth opening was still the technique participants felt more confident using (95 to 97%). In community dental services and hospital settings, Mallampati was the most well known test (70% and 85% respectively). This may be due to the fact that, historically, Mallampati has been a common technique taught when considering airway assessment, which is reinforced by the findings in anaesthetics which also found Mallampati to be frequently recorded in preoperative assessments.16,17,18

In hospital settings, clinicians found both mouth opening and S.T.O.P. B.A.N.G. the most useful techniques for airway assessment, which may reflect the more complex patient base seen as well as the increasing number of studies on obstructive sleep apnoea and its correlation with difficult airway and complications.

11% of participants (n = 28) had experienced an incident where a patient suffered airway obstruction or hypoxia and felt an airway assessment could have predicted the incident. This further reinforces the necessity of carrying out airway assessment in sedation as airway-related complications can occur and reinforces the need to identify patients with an increased risk of airway difficulties. Clinicians should be able to identify suitable cases for management in general practice and confidently refer where secondary care input is required.19

Participants were asked what factors would prompt them to use an airway assessment tool routinely and the most common theme identified was clinical indication. This implies that when factors are present which may be predictive of a difficult airway, they would then be more likely to carry out a formalised technique and document their findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study shows that non-anaesthetist sedationists in dentistry have the knowledge and confidence to perform airway assessment and the majority do routinely carry this out. However, as current guidelines state that clinicians practising conscious sedation in dentistry do need to carry out airway assessment for all patients, a change in practice is still required. This study also highlights that documentation of airway assessment requires improvement. Mouth opening was the technique that most participants knew, used, felt confident in using and found the most useful. This is in contrast with the literature, which shows mouth opening is a poor predictor for the difficult airway.

This study has also shown that although very safe, airway-related complications do occur within conscious sedation in dentistry as 11% of clinicians had experienced an airway-related incident where airway assessment could have prevented this. This reinforces the need to ensure an airway assessment is carried out for all patients. It also recognises the need for good reporting systems and transparency within dentistry so that more accurate details can be obtained regarding adverse incidents in conscious sedation.

Difficulties will be encountered when considering how airway assessment should be undertaken in dentistry as there is no universally accepted airway assessment tool or technique that is the most predictive of a difficult airway. Developing a tool predictive of a rare outcome is difficult due to the need for large numbers, likely over a long time period, to show significant findings. However, there is a clear desire for training in this area and better knowledge of the tools and techniques available. A nationally recognised airway assessment resource summarising core airway management considerations, essential components of a routine airway assessment and advising a structured approach specifically for dental sedation may empower clinicians to determine the appropriate manner in which to assess their patients and carry out sedation safely.

References

1. Humphris G, Crawford J R, Hill K, Gilbert A, Freeman R. UK population norms for the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale with percentile calculator: Adult Dental Health Survey 2009 Results. BMC Oral Health. 2013; 13:29.

2. Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry. Standards for Conscious Sedation in the provision of Dental Care( V1.1). 2020. Online information available at http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/dental-faculties/fds/ publications-guidelines/standards-for-conscious-sedation-in-the-provision-of- dental-care-and-accreditation/ (accessed September 2023).

3. Corcuera-Flores J, Silvestre-Rangil J, Cutando-Soriano A, Lopez-Jimenez J. Current methods of sedation in dental patients - A systematic review of the literature. Medicina Oral Patología Oral y Cirugia Bucal 2016; 21:579-86.

4. Wilson K. Vital guide to conscious sedation. Vital 2008; 5:19–22.

5. Craig D, Boyle C A. Practical conscious sedation. 2nd ed. London; Quintessence Publishing, 2017.

6. Girdler NM , Hill C M, Wilson K E. Conscious sedation for dentistry. 2nd ed. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2017.

7. Girdler N, Wilson K, Booth E. A prospective study of complications and outcomes associated with conscious sedation for the anxious dental patient. Journal of Disability and Oral Health 2015; 6: 24–30.

8. Shehabi Z, Flood C, Matthew L. Midazolam use for dental conscious sedation: how safe are we? Br Dent J 2018;224:98–104.

9. Wilson K E, Thorpe R J, McCabe J F, Girdler N M. Complications Associated with Intravenous Midazolam Sedation in Anxious Dental Patients. Primary Dental Care 2011; 18:161–6.

10. Office of Chief Dental Officer England.Commissioning Dental Services: Service standards for Conscious Sedation in a primary care setting. 2017. Online information available at https://www.sdcep.org.uk/media/iota3oqm/sdcep-conscious-sedation-guidance-unchanged-2022.pdf (accessed September 2023).

11. Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP). Conscious sedation in Dentistry: Dental clinical guidance. 2022. Online information available at https://www.sdcep.org.uk/media/iota3oqm/sdcep-conscious-sedation-guidance-unchanged-2022.pdf (accessed September 2023).

12. Hester C E, Dietrich S A, White S W, Secrest J A, Lindgren K R, Smith T. A comparison of preoperative airway assessment techniques: the modified Mallampati and the upper lip bite test. AANA J 2007;75:177-82.

13. Ambesh S P, Singh N, Rao P B, Gupta D, Singh P K, Singh U. A combination of the modified Mallampati score, thyromental distance, anatomical abnormality, and cervical mobility (M-TAC) predicts difficult laryngoscopy better than Mallampati classification. Acta Anaesth Taiwanica 2013;51:58–62.

14. Ji S M, Moon E J, Kim T J, Yi J W, Seo H, Lee B J. Correlation between modified LEMON score and intubation difficulty in adult trauma patients undergoing emergency surgery. World journal of emergency surgery: WJES 2018;13:33.

15. Lee A, Fan L T, Gin T, Karmakar M K, Ngan Kee W D. A systematic review (meta- analysis) of the accuracy of the Mallampati tests to predict the difficult airway. Anesth Analg 2006;102:1867–78.

16. Mellado P F, Thunedborg L P, Swiatek F, Kristensen M S. Anaesthesiological Airway Management in Denmark: Assessment, equipment and Documentation. Acta Anaesth Scand 2004;48:350–4.

17. Waddington M S. Book review: NAP4. 4th National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the difficult airway society. Major complications of airway management in the United Kingdom. Report and findings March 2011. Anaesth Int Care 2011;39:1165–6.

18. Vannucci A, Cavallone L F. Bedside predictors of difficult intubation: a systematic review. Minerva Anestesiol 2016;82:69-83.

19. Owen B, Bradley H. Airway Assessment for Intravenous Sedation in Dentistry. Dental Update 2022;49:52–6.