Please click on the tables and figures to enlarge

Do children from more deprived backgrounds have a higher chance of becoming dentally anxious?

L. J Irving, BSc (Hons), PGCE1

1 Final Year Dental Student, University of Central Lancashire, School of Dentistry, AllenBuilding, Preston, PR1 2HE

Correspondence to: Laura Irving

Email: lirving2@uclan.ac.uk

Irving L J. Do children from more deprived backgrounds have a higher chance of becoming dentally anxious? SAAD Dig. 2024: 40(1): 77-80

Abstract

There is certainly no shortage of literature surrounding the incidence of dental anxiety, the causes of dental anxiety and management strategies. Similarly, much research has been undertaken to investigate the relationship between socioeconomic position and dental disease rates. Both anxiety and a lower socioeconomic position have been linked with poorer oral health-related quality of life. We know that early childhood dental experiences can set the tone for a patient’s attitudes towards, and relationships with, dentists and dental treatments. The aim of this review was to investigate whether children from a lower socioeconomic position are more likely to become dentally anxious. It aims to explore whether the treatment of children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds is different to their more affluent peers and, if so, whether this might impact how these individuals go on to perceive dentists and dental treatment. As dentists we must provide appropriate treatment and aim for the best dental health outcomes, whilst also considering the patient holistically. With children, this should involve fostering positive relationships and dental experiences where possible, to set them up for a positive and healthy dental future which is as anxiety free as possible.

Introduction

Dental anxiety is a common issue faced by many individuals across the globe and the UK is no exception.1,2 Severe dental anxiety or phobia can have serious implications for an individual, including dental avoidance and subsequently poor oral health (OH). High levels of dental anxiety have been implicated in lower quality of life, higher incidence of caries, more missing teeth and fewer filled teeth.3,4 Dentists must, of course, carry out treatments which serve the purpose of ensuring dental health, but consideration should also be given to the overall wellbeing of the patient, particularly with regards to anxiety in children. Childhood dental experiences set the tone for attitudes towards dental treatments in future life, with negative experiences having potentially huge detrimental effects on an individual.5,6 For the dental profession, it would make sense to eliminate anxiety where possible. High patient anxiety can present huge barriers to dental treatment for the patient, whilst also being difficult to manage for the dental team in terms of time, resources and emotion. Both dental anxiety and low socioeconomic position (SEP) have been proven to represent barriers to obtaining necessary treatment independently.7-9 In the ethos of health equity we should be aiming to break these down these barriers wherever possible. The aim of this review therefore was to explore the peer-reviewed literature to answer the question ‘do children from more deprived backgrounds have a higher chance of becoming dentally anxious?’

Background

Many definitions of dental anxiety exist within the literature, but for the purposes of this review it will be considered as fear and anxiety towards the dentist and dental treatment. Dental phobia is a more extreme fear, where a person can experience an overwhelming, all-consuming fear of the dentist and will sometimes avoid visits or treatment completely. Where anxiety or phobia are so strong that they lead to evasion of treatment, this can promote poor Oral Health (OH), causing a reduction in oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL).10 Dental anxiety has been cited as the fifth most common cause of anxiety.1

A literature review carried out in 2014 found that the causes of dental anxiety and dental phobia are multifactorial.12 They can include exogenous factors such as traumatic experiences and learning through significant others, but also endogenous factors such as personality traits or inheritance. Of particular importance to children, is parental dental anxiety levels. One recent randomised control trial (RCT) carried out found that children whose parents were dentally anxious displayed more anxious behaviours than counterparts with non-anxious parents.13 With the incidence of dental anxiety and dental phobia combined estimated as being around 46% of the UK adult population,1 management of anxious patients is something every dentist is likely to have some degree of experience in. The Children’s Dental Health Survey 2013 found that 76% of 12-year-olds in the UK had moderate or extreme dental anxiety, along with 64% of 15-year- olds. This was lower in the younger age groups, with 21% and 17% of five and eight-year-olds affected respectively.2

Socioeconomic position (SEP) is a phrase which refers to the social and economic factors influencing the position that individuals or groups hold within the structure of a society. Education, income and social class based on occupation are three common markers of social class thought to influence a person’s SEP.14 Education relates to the knowledge and skills gained through the highest level of education or schooling achieved. Income measures an individual’s material assets, whilst occupation tends to reflect a person’s social standing and is often closely linked with income or material resources.

When considering deprivation, further measures exist. The four which are most used are: Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD)15 Jarman Underprivileged area score,16 Townsend Index17 and Carstairs Index.18 IMD is perhaps the most frequently encountered and in England is based on a cumulative model of seven domains.19 IMD rankings are based on a weighted cumulative model of these seven domains. Scores are assigned to 32,844 neighbourhoods or areas in England to give a relative score of deprivation, where neighbourhood number one is the least deprived, and number 32,844 the most deprived. It is important to note that just because an individual lives in a deprived (or affluent) area, this does not mean their individual status is one which is deprived (or affluent).

Speaking broadly, management options for dentally anxiouspatients are psychotherapeutic, pharmacological or a combination of the two. Which option is chosen can depend on the level of anxiety, patient wishes, medical history and the clinical situation. Psychotherapeutic options are either cognitively or behaviourally focussed, meanwhile pharmacological options are sedation, (inhalational [IHS] or intravenous [IV] or general anaesthesia [GA]).7

Within the NHS, a referral can be made to specialist sedation services, where dentists have undertaken a degree of further training to be able to provide IV midazolam sedation. It must be noted, however, that the NHS target is that 92% of those referred into secondary care are seen within 18 weeks,20 which is a considerable amount of time for someone with acute dental pain. Availability of an emergency dental appointment may mean a patient can be seen quicker, but a suitable method for anxiety control may not be available. Accessibility to these services can also depend on geography and, as such, not all treatment options are reliably available to the whole population. Furthermore, according to one Trust, only basic conservative treatment and extractions will be carried out under sedation, which does not include endodontic treatment of posterior teeth.21 It can be inferred therefore, that the likely treatment option for posterior teeth with irreversible pulpitis would be extraction.

GA carries serious risks including morbidity and very rarely, mortality, so to minimise the need for further GA episodes, the most common treatment carried out is exodontia.22 Though radical, this eradicates the risk of secondary caries and the need for further treatment on teeth affected by caries.

Many practitioners now offer IV sedation privately, allowing patients to be seen more quickly, and perhaps offering more extensive treatment options than those offered by NHS sedation. However, a sedation session alone (not including any treatment) can cost from £250 per hour upwards. This option is therefore limited to those with the financial means to engage with these services.

Oral health status of children across the socioeconomic gradient

A new definition of OH was proposed by the World Dental Federation in 2017:

‘Oral health is multi-faceted and includes the ability to speak, smile, smell, taste, touch, chew, swallow and convey a range of emotions through facial expressions with confidence and without pain, discomfort and disease of the craniofacial complex.’ 24

OH status amongst children in the UK is a highly variable and a complex matter. When considering child dental health, this is normally through the incidence of dental decay or caries, since periodontal disease (other than gingivitis) is an uncommon finding in children.25 A dental epidemiology survey of five-year-old children carried out by Public Health England (PHE) found that 25% of participants had tooth decay, with an average of 3 or 4 affected teeth.26 Areas with poorer OH tended to be in the north of the country and in more deprived localities. Rates of decay were highest in Blackburn and Darwen where 56% of children were affected, and lowest in South Gloucester were just 4% were affected. The same survey showed that 41% of variation in severity of dental caries can be explained by deprivation.26 The Child Dental Health Survey found that children who were from more deprived backgrounds (as assessed by eligibility for free school meals) were more likely to suffer from dental decay than their more affluent counterparts in all the age groups sampled.2

Children with poor OH are more likely to suffer from pain and infection, eating and sleeping difficulties and an overall negative effect on their wellbeing. They are likely to have time off school, which can also mean parents or carers having to take time off work to take them for treatment. Tooth decay remains the highest- ranking reason for hospital admission in the six to ten age group.27 In the year 2018-19, there were some 37,406 procedures carried out in hospitals for the extraction of carious teeth in children aged one to 19 years old.27 Pain and negative treatment experiences are closely linked with dental anxiety7,8 and both disproportionately affect children from more deprived backgrounds.

Treatment of decay in children across the socioeconomic gradient

The Children’s Dental Health Survey2 investigated rates of teeth missing due to decay, as well as teeth which were restored or were requiring restorations. However, when making comparisons between groups, the survey only compared these aspects across age groups and countries and did not assess for differences between those eligible and not eligible for free school meals, as it did with other components of dental health.

One survey did investigate dental care indices across regions in England. Dental care index was defined as being the percentage of teeth with decay experience, that have been restored. This was significantly lower in areas where dental caries rates were high. For example, the northwest of England had a care index of approximately 7%, whilst in the southeast of England, this was around 14%.27 It is interesting that where caries experience is high, restorative activity is low, as this could suggest that carious teeth are being treated either by extraction or left untreated.

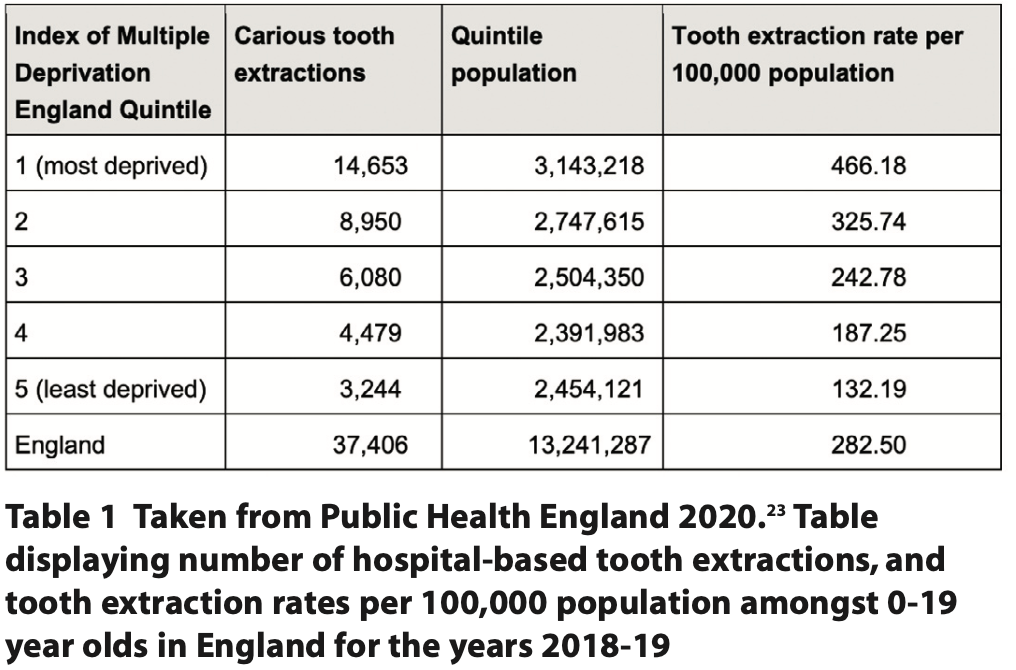

The table below comes from PHE and displays the number of teeth extracted in hospitals across the five deprivation quintiles, as well as tooth extraction rates. Those in the most deprived quintile are more than three times more likely to have dental extractions carried out in hospitals than those in the least deprived quintile. Often, hospital extractions are carried out under a general anaesthetic and are a child’s first introduction to dental care. This can lead to fear and anxiety around dental treatment, with lifelong consequences.7 Again, this appears to be something which disproportionately affects children from more deprived backgrounds.27

One study found that children from deprived backgrounds who regularly attended a group of UK dentists were more likely to have extractions than their more affluent peers, irrespective of their caries, pain or sepsis experience.28 These results suggest that dentists are prescribing prophylactic extractions in children from poorer backgrounds. There are several reasons why a dentist may choose to carry out a more definitive treatment such as extraction in response to oral disease. These may include concerns about future attendance / compliance or concerns about systemic illness if infection progresses. Parental pressures may also play a role. Parents of children from more affluent backgrounds are more likely to expect and demand treatments other than extractions, whereas those from deprived backgrounds are more likely to accept extraction of primary teeth as a reasonable option.29

Dental anxiety levels across socioeconomic backgrounds

The 2011 Adult Dental Health Survey1 involved a total of 13,400 households and so offered a reasonably good insight into the UK population as a whole. From this survey, it was deduced that those suffering from dental phobia are more likely to have a lower educational attainment, which is directly linked with the other measures of SEP, income and occupation.

Milsom, Tickle, Humphris and Blinkhorn found that there were several factors relating to dental anxiety in five-year-old children. Those that were dentally anxious were significantly more likely to have undergone dental extraction(s), have more caries experience and to have anxious parents.30 They also found that after controlling for other factors, a history of restoration did not significantly influence incidence of anxiety. In addition, when Merdad and El-Housseiny explored previous dental experience on OHRQoL in children, they found that receiving fillings at previous dental visits was associated with a better OHRQoL, whilst pain was associated with a poorer OHRQoL.31

Discussion

Dentists are qualified professionals, who are trained in the planning and delivery of appropriate treatments for a range of dental diseases. It is of course necessary in some instances to carry out treatment which may be unpleasant or traumatic if this is deemed in the best interests of a patient. This is particularly important with regard to provision of treatment under a general anaesthetic, where treatments are often more radical in order to avoid the need for further general anaesthetics in the future due to its associated risks. The Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP) provides guidance for the appropriate management of dental issues such as irreversible pulpitis.32 It also states that for children with carious lesion(s) in primary teeth, it is strongly recommended to choose the least invasive, feasible caries management strategy. Whilst it would be nice to believe that this is occurring, the results of one study28 are particularly worrying, suggesting that perhaps this is not the case and that children from more deprived backgrounds are undergoing more extractions in general practice, irrespective of their caries experience, than their more affluent counterparts. Extraction of teeth is an invasive and unpleasant experience which has been proven to be linked with long-term consequences such as dental anxiety and poor attendance.33 These prescribing patterns are therefore producing an inequitable predisposition to dental anxiety in those children from poorer backgrounds, potentially contributing to future issues with dental anxiety or phobia. Of course, this is just one study, but it does pose questions about whether this is something which should be investigated in other parts of the UK.

That parental pressures may play a role in treatment options for children is concerning when this affects the most deprived children in society unfairly. It is the dental team who hold the appropriate knowledge and skills with regards to which treatment options are best for managing dental problems. Of course, parents and carers should be involved in the decision-making process, but it seems unfair that a deprived child may receive less preferential treatment owing to the fact they may not have a parental advocate.

The role of prevention, particularly for those children who are amongst the most deprived in society, cannot be understated. Not only do preventive practices minimise risk of disease, bringing about the multitude of benefits associated with this, but they should also be considered as means of preventing patient anxiety. Preventive practices such as fluoride varnish application and placement of fissure sealants are effective in caries prevention,34 but also serve acclimatisation purposes as they are relatively non- invasive. These early interventions therefore serve a dual beneficial purpose.

Conclusions

SEP and caries experience are closely related, as has been shown across the literature.7-9 This means that children in a lower SEP are more likely to have caries experience than their more affluent peers. These children are also more likely to suffer from pain and sepsis due to this.30 There is some evidence to suggest that children from deprived backgrounds are treated in more radical ways than their more affluent peers, with extraction being a preferred treatment option regardless of caries, pain or sepsis experience.

Social mobility in the UK remains among the poorest in all the developed nations,35 meaning that for those born into a family with a low SEP, they are likely to remain there for the remainder of their lives. Not only then are these individuals at higher risk of dental disease as children, but they are highly likely to carry this risk with them throughout their lives. Higher caries and periodontal disease incidence equate to the need for more extensive dental treatments, which can be unpleasant.

Unfortunately, this means that those from a lower SEP are more likely to be affected by a double blow of extensive treatments which can lead to anxiety in childhood through to adulthood and higher caries rates (involving pain, sepsis) which can also lead to anxiety.

Areas for further investigation or consideration may be:

- Are children from deprived backgrounds less likely to receive restorative treatment for teeth than their more affluent counterparts?

- Are more radical treatment options undertaken for children from deprived backgrounds?

- And if so, are these justified?

- Should deprivation status of a child be considered as an explicit risk factor for dental disease and development of dental anxiety when assessing patients?

- Should a more effective prevention programme be set up specifically for deprived children on the NHS, free of charge to patients?

- Could a similar investigation be undertaken to identify a relationship between SEP and dental anxiety in adults?

Ultimately, children from lower SEPs are much more likely to experience the main risk factors for development of dental anxiety than their more affluent peers. Though this is the current state of play, as a profession it is not something which we should simply accept and, in the interests of health equality and equity, this should be investigated further. It seems unacceptable that in 21st century Britain, a child is more likely to go on to not only suffer poor OH, but also to be more likely to have higher levels of anxiety when receiving treatment for this, owing to the SEP into which they were born.

References

1. Adult Dental Health Survey – Summary report and thematic series. London: Government Statistical Service, NHS Digital, 2011.

2. Children’s Dental Health Survey 2013 – Report 1: Attitudes, Behaviours and Children’s Dental Health. London: Government Statistical Service NHS Digital, 2015.

3. McGrath C, Bedi R. The association between dental anxiety and oral health- related quality of life in Britain. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2004; 32: 67–72.

4. Coriat I H. Dental anxiety: fear of going to the dentist. Psychoanal Rev 1946; 33:365–367.

5. Olivera M A, Vale M P, Bendo C B, Paiva S M, Serra-Negra J M. Influence of negative dental experiences in childhood on the development of dental fear in adulthood: a case-controlled study. J Oral Rehabil 2017; 44: 434-41.

6. Townend E, Dimigen G, Diane F. A clinical study of dental anxiety. Behav Res Ther 2000; 38: 31-46.

7. Appukuttan D P. Strategies to manage patients with dental anxiety and dental phobia. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent 2016; 8:35-50.

8. Gatchell R J, Ingersoll B D, Bowman L, Robertson M C, Walker C. The prevalence of dental fear and avoidance: a recent survey study. J Am Dent Assoc 1983; 107: 609–610.

9. Timis T, Danila I. Socioeconomic status and oral health. J Prevent Med 2005; 13:116-21.

10. Carter A E, Carter G, Boschen M, Al-Shwaimi E, George R. Pathways of fear and anxiety in dentistry: a review. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2:642–53.

11. Agras S, Sylvester D, Oliveau D. The epidemiology of common fears and phobia. Compr Psychiatry 1969; 10: 151-6.

12. Beaton L, Freeman R, Humphris G. Why are people afraid of the dentist? Observations and explanations. Med Princ Pract 2014; 23: 295–301.

13. Yigit T, Topal B C, Ozgocmen E. The effect of parental presence and dental anxiety on children’s fear during dental procedures: A Randomised Trial. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2022; 27: 1234-45.

14. Darin-Mattsonn A, Fors S, Kareholt I. Different indicators of socioeconomic status and their relative importance as determinants of health in old age. Int J Equity Health 2017; 173.

15. The English Indices of Multiple Deprivation 2019 (IoD 2019) National Statistics, Gov UK 2019. London: Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, 2019.

16. Jarman B. Identification of underprivileged areas. Br Med J 1938: 1705-1709.

17. Townsend P. Deprivation. J Soc Policy 1987; 16: 125-146.

18. Carstairs V, Morris R. Which deprivation? A comparison of selected deprivation indexes. J Public Health Med 1991; 13: 318–326.

19. The English Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2015 – Guidance. London: Department for Communities and Local Government, 2015.

20. NHS England. Guide to NHS Waiting Times in England. 2019. Online information available at: https://www.nhs.uk/nhs-services/hospitals/guide-to-nhs-waiting-times-in-england/ (accessed February 2023).

21. Barts Health NHS Trust. Sedation Acceptance Criteria. 2023. Online information available at https://dental.bartshealth.nhs.uk/referrals-sedation (accessed February 2023).

22. Knapp R, Marshman Z, Rodd H. Treatment of dental caries under general anaesthetic in children. BDJ Team 2017; 4.

23. Hospital tooth extractions of 0-19 year olds. London: Public Health England, 2020.

24. Glick M, Williams D M, Kleinman D V, Vujicic M, Watt R G,Weyant R J. A new definition for oral health developed by the FDI World Dental Federation opens the door to a universal definition of oral health. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016; 147: 915- 17.

25. Al-Ghutaimel H, Riba H, Al-Kahtani S, Al-Duhaimi S. Common periodontal diseases of children and adolescents. Int J Dent, 2014.

26. National Dental Epidemiology Programme for England: oral health survey of 5- year-olds 2019: A report on the variations in prevalence and severity of dental decay. London: Public Health England, 2020.

27. Inequalities in oral health in England, full report. London: Public Health England, 2021.

28. Tickle M, Milsom K, Blinkhorn A. Inequalities in the dental treatment provided to children: An example from the UK. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol 2002; 30: 335-41.

29. Hood C A, Hunter M L, Kingdon A. Demographic characteristics, oral health knowledge and practices of mothers of children aged 5 years and under referred for extraction of teeth under general anaesthesia. Int J Paediatric Dent 1998; 186: 131-6.

30. Milsom K M, Tickle M, Humphris G M, Blinkhorn A S. The relationship between anxiety and dental treatment experience in 5-year-old children. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 503-6.

31. Merdad L, El-Housseiny A A. Do children’s previous dental experience and fear affect their perceived oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL)?. BMC Oral Health 2017; 47.

32. Prevention and management of dental caries in children second edition, Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. Online information available at: https://www.sdcep.org.uk/published-guidance/caries-in-children/ (accessed February 2023).

33. Bridgman C M, Ashby D, Holloway P J. An investigation of the effects on children of tooth extraction under general anaesthesia in general dental practice. Br Dent J 1999;189:494-9.

34. Public Health England. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. London: Public Health England, 2021.

35. Social Mobility Commission. State of the Nation 2022. A fresh approach to social mobility. London: Social Mobility Commission, 2022.