Please click on the tables and figures to enlarge

Case report: A paediatric patient with molar incisor hypomineralisation and hypodontia, treated with inhalation and intravenous sedation for extractions of deciduous and permanent molars

T. Ng BDS*

Specialist Trainee Registrar in Special Care Dentistry, Shropshire Community Dental, 71 Castle Foregate, Shrewsbury SY1 2EJ

*Correspondence to: Teresa Ng

Email: Teresa.ng2@nhs.net

Ng T. Case report: A paediatric patient with molar incisor hypomineralisation and hypodontia, treated with inhalation and intravenous sedation for extractions of deciduous and permanent molars. SAAD Dig. 2024: 40(1): 54-56

Case Summary

A 12-year-old patient was referred into the community dental service by their general dental practitioner following an orthodontic opinion. Clinical and radiographic examination revealed molar incisor hypomineralisation with grossly broken down UR6 and UL6. In addition to hypodontia, the LL5 was not present and a retained LLE was in situ. The patient was advised removal of UL6, UR6, LLE, LRE by the orthodontist. The patient had never received dental treatment and was anxious. The patient successfully completed treatment with inhalation sedation for the removal of LRE and LLE and intravenous sedation for the removal of UR6 and UL6.

Patient details

Gender: female

Age at start of treatment: 12 years old

Pre-treatment assessment

History of presenting patient’s complaints: Patient had pain on eating for a few months, associated with the upper posterior teeth. No history of swelling or disturbed sleep. Relevant medical history: Patient was medically fit and well, with no allergies.

Dental history: Patient was a regular dental attender at the GDP every six months. Patient had not received dental treatment in the past.

Clinical examination: Good oral hygiene. Molar incisor hypomineralistion, with post eruptive breakdown and caries in the UR6 and Ul6. Mild hypodontia: LL5 not present . No clinical photographs were taken, as it is not a routine practice within the community dental service.

General radiographic examination:

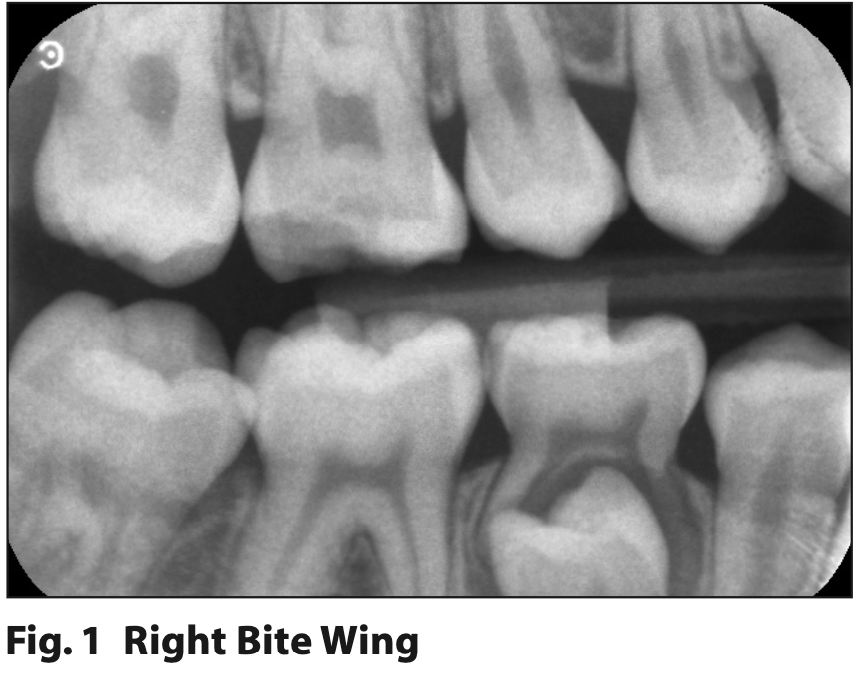

Date taken: 15th November 2021

Date taken: 15th November 2021

Quality rating: Acceptable

Date taken: 15th November 2021

Quality rating: Acceptable

Date taken: 13th July 2021

Quality rating: Acceptable

Radiographic findings from bitewings and OPT:

- UR6 large mesial radiolucency close to the pulp

- UL6 large mesial radiolucency close to the pulp

- LL5 not present

- LLE retained with root resorption.

- UR8 / UL8 / LL8 / LR8 unerupted follicles present

Diagnostic summary

- Hypodontia – LL5 not present, retained LLE

- Molar incisor hypomineralistion – affecting all incisors and molars, UR6 and UL6 grossly broken down

Aims and objectives of treatment

- To maintain good oral hygiene and diet

- To provide dental treatment as advised by orthodontic treatment plan for the removal of UL6, UR6, LLE, LRE

- To provide treatment in a modality which the patient can accept.

Treatment plan

- Oral hygiene and diet advice for a low caries risk patient, in accordance with Delivering Better Oral Health1

- Removal of UR6, UL6, LRE, LLE indicated on referral by orthodontist and the general dental practitioner. Treatmentmodality options were discussed along with their respective risks and benefits. The patient chose to undergo the treatment under inhalation sedation, with written parental consent obtained.

Treatment undertaken

i. LRE and LLE removed under inhalation sedation, as the patient wanted to reduce the appointments required.

- Titrated to 35% nitrous oxide with 5 L/min flow

ii. Patient struggled with the pressure of the deciduous tooth extractions and requested an alternative modality for the

removal of the UL6 and UR6. Patient and parent decided to proceed with intravenous sedation and the patient was

reassessed for IV sedation with midazolam

iii. UL6 and UR6 removed under intravenous sedation

- Titrated 4 mg midazolam against response

- Sedation scoring 2 as the patient was drowsy, with fair operating conditions and minimal interference.

Long term treatment and future considerations

Patient has good oral hygiene and diet, and has been discharged to their general dental practitioner for continuing dental care and to the orthodontist to receive further treatment.

Discussion and reflection

Molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH) is a common developmental dental condition, which results in poorly formed enamel in the first permanent molars and opacities in anterior teeth. It has both a functional and social impact on children, as the affected teeth can be sensitive to thermal or mechanical stimuli and at a higher risk of caries. The involvement of a multidisciplinary team is essential for short and long-term planning, in particular the role of an orthodontist in planning extractions.2

The patient was referred by their general dental practitioner and had been assessed by the orthodontist. The orthodontist discussed the treatment options with the patient and the parent. They discussed retaining the lower left deciduous molar which was not mobile and at the correct occlusal level. However, it may eventually be lost, upon which the patient would have a space that could be accepted or the space could be restored with a denture, bridge or implant. The alternative was to choose to extract both upper first permanent molars (FPM) and both lower deciduous second molars and to proceed with fixed appliances to align the arches and close the space. The patient and parent chose the latter option.

The patient presented with MIH affecting both upper FPM and upper central permanent incisors. The European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry (EAPD) defines the diagnostic criteria and clinical appearance of the defects, by which one to four of the FPM must be affected, simultaneously the permanent incisors can also be affected.3 The teeth may present with demarcated opacities or enamel disintegration; they may exhibit atypical restorations and patients may experience tooth sensitivity. Extracted teeth can only be defined as MIH if as previously documented.

The EAPD defines mild MIH to be demarcated enamel opacities without enamel breakdown, sensitivity induced by external stimuli and mild aesthetic concern. Severe MIH is defined as demarcated enamel opacities with breakdown and caries, with spontaneous hypersensitivity and strong aesthetic concern.3

This patient presented with enamel opacities on her upper central permanent incisors which were determined as mild in the severity level using the EAPD criteria, whereas demarcated enamel disintegration with caries on both upper FPM would be classified as severe. The aesthetic presentation of the upper first permanent incisors did not concern the patient and therefore we discussed and decided this would be managed by their general dental practitioner.

The recognition of the compromised FPM due to MIH and hypodontia without acute pathology or pain led to the multidisciplinary treatment of this patient which is in line with the guidance for the extraction of FPM by the Royal College of Surgeons of England.4

The guidance advises:

- The assessment of compromised FPM to plan for extractions

- The extraction of the FPM for spontaneous second permanent molar (SPM) space closure between eight to ten years of age which may not be possible due to symptoms and pathology

- The involvement of the orthodontic and paediatric team is recommended where possible

- Balancing and compensating extractions are not recommended routinely for FPM.

The indication for the removal of both upper FPM is due to MIH with a poor long-term prognosis, there would be limited spontaneous SPM space closure due to her age and the presence of the SPM. However, for this patient, space closure is planned by the orthodontist using fixed appliances due to the hypodontia present.

The patient had never received dental treatment and expressed anxiety over dental extractions. After exploring different treatment modalities, the patient was willing to accept dental treatment under inhalation sedation (IHS) with nitrous oxide. This technique is safe and effective for children as an adjunct to behaviour management.5,6 Due to the patient’s anxiety, we discussed attempting the removal of the lower deciduous second molars first prior to the upper FPM. IHS was successful for managing the patient’s anxiety regarding local anaesthetic, however, for the removal of the lower second deciduous molars (LRE and LLE) the patient found it difficult to tolerate the pressure associated with the extraction.

Following the removal of the deciduous teeth, the patient was too anxious to proceed with inhalation sedation for the removal of the UR6 and UL6. The patient was reassessed and we explored the remaining treatment modalities of either intravenous sedation (IVS) or general anaesthetic (GA). The patient and the mother decided to proceed with IVS using midazolam, and written consent was obtained. The patient was not anxious about cannulation as she had previously accepted venepuncture. IVS has a good rate of success in managing dental anxiety for young people and adults and offers an alternative to GA, thus reducing risks and GA waiting lists.7,8 There have been no reported significant side effects recorded in paediatric patients under IVS, the main side effect being a paradoxical reaction.9

The patient successfully had UR6 and UL6 removed in one visit under IVS and was discharged back to the care of their general dental practitioner and orthodontist.

Conscious sedation is an important adjunct to behaviour management for dental patients. For paediatric patients, patient assessment in addition to the engagement of the parents or guardians is essential to facilitate a positive dental journey. It is important to consider the use of different sedation techniques as appropriate for each individual patient.10,11

References

1. Delivering better oral health. Online information available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/delivering-better-oral-health-an-evidence-based-toolkit-for-prevention (accessed October 2023).

2. Rodd H D, Graham A, Tajmehr N, Timms L, Hasmun N. Molar Incisor Hypomineralisation: Current Knowledge and Practice. Int Dent J. 2021 Aug;71:285-291.

3. Lygidakis N A, Garot E, Somani, C., Taylor G D., Rouas P. and Wong, F S L. Best clinical practice guidance for clinicians dealing with children presenting with molar-incisor-hypomineralisation (MIH): an updated European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry policy document. European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry 2021.

4. The Royal College of Surgeons of England. (2023). A Guideline for the Extraction of First Permanent Molars in Children. [online] Available at: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/FDS/Guidance-for-the-extraction-of-first-permanent-molars-in-children.pdf (accessed October 2023).

5. Paterson S A, and Tahmassebi J F. Paediatric dentistry in the new millennium: 3. Use of inhalation sedation in paediatric dentistry. Dent Update. 2003;30:350-6, 358.

6. Lourenço-Matharu L, Ashley P F and Furness S. Sedation of children undergoing dental treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; Mar 14;(3).

7. Anand P, Lyne A, Fulton A, Tanday A and Chaudhary M. Service evaluation of an intravenous sedation service within a hospital paediatric dentistry unit: ten-year results. Br Dent J. 2021 Jan 21.

8. Wallace A, Hodgetts V, Kirby J, Yesudian G, Nasse H, Zaitoun H, Marshman Z, Gilchrist F. Evaluation of a new paediatric dentistry intravenous sedation service. Br Dent J. 2021 Mar 11.

9. Papineni McIntosh A, Ashley P F and Lourenço-Matharu L. Reported side effects of intravenous midazolam sedation when used in paediatric dentistry: a review. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2015;25:153-64.

10. SAAD. Online information available at https://www.saad.org.uk (accessed August 2022).

11. SCDEP. Online information available at https://www.sdcep.org.uk/published-guidance/conscious-sedation/ (accessed August 2022).